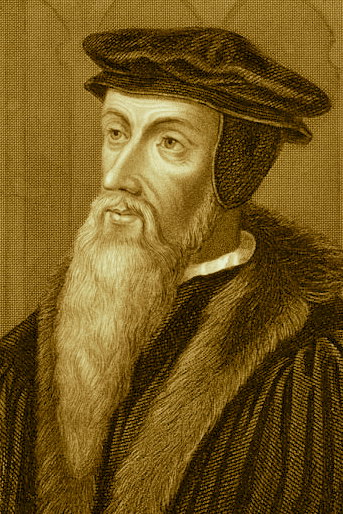

Reflecting on common grace and intellectual exploration, I found the book “God and the Cosmos: Divine Activity in Space, Time and History” by Harry Lee Poe and Jimmy H. Davis to be a helpful read. The authors set the tone for their exploration by invoking a quote from the 16th century theologian John Calvin, a voice echoing from the pages of his seminal work, “Institutes of Christian Religion,” first published in 1536. I likely read this section in my “Calvin’s Institutes” course I took at Calvin College but I’m sure would not have taken note at the time.

Today this Calvin quote resonates deeply with me: “If we reflect that the Spirit of God is the only fountain of truth, we will be careful, as we would avoid offering insult to him, not to reject or condemn truth wherever it appears. In despising the gifts, we insult the Giver.”

This quote captures the essence of a timeless truth—that the pursuit of knowledge and the recognition of truth are intricately intertwined with divine wisdom.

As I read Poe and Davis’s exploration expanding on this I wondered if they had captured the full context of Calvin’s words. Consulting sections 2.2.236 and 2.2.237 of the Institutes of Christian Religion, I found deeper understanding of the theological underpinnings surrounding the appreciation of truth and knowledge in Calvin’s worldview.

Below I provide an extended quote from Calvin.

Next come manual and liberal arts, in learning which, as all have some degree of aptitude, the full force of human acuteness is displayed. But though all are not equally able to learn all the arts, we have sufficient evidence of a common capacity in the fact, that there is scarcely an individual who does not display intelligence in some particular art. And this capacity extends not merely to the learning of the art, but to the devising of something new, or the improving of what had been previously learned. This led Plato to adopt the erroneous idea, that such knowledge was nothing but recollection. So cogently does it oblige us to acknowledge that its principle is naturally implanted in the human mind. But while these proofs openly attest the fact of a universal reason and intelligence naturally implanted, this universality is of a kind which should lead every individual for himself to recognize it as a special gift of God. To this gratitude we have a sufficient call from the Creator himself, when, in the case of idiots, he shows what the endowments of the soul would be were it not pervaded with his light. Though natural to all, it is so in such a sense that it ought to be regarded as a gratuitous gift of his beneficence to each. Moreover, the invention, the methodical arrangement, and the more thorough and superior knowledge of the arts, being confined to a few individuals cannot be regarded as a solid proof of common shrewdness. Still, however, as they are bestowed indiscriminately on the good and the bad, they are justly classed among natural endowments.

Therefore, in reading profane authors, the admirable light of truth displayed in them should remind us, that the human mind, however much fallen and perverted from its original integrity, is still adorned and invested with admirable gifts from its Creator. If we reflect that the Spirit of God is the only fountain of truth, we will be careful, as we would avoid offering insult to him, not to reject or condemn truth wherever it appears. In despising the gifts, we insult the Giver. How, then, can we deny that truth must have beamed on those ancient lawgivers who arranged civil order and discipline with so much equity? Shall we say that the philosophers, in their exquisite researches and skillful description of nature, were blind? Shall we deny the possession of intellect to those who drew up rules for discourse, and taught us to speak in accordance with reason? Shall we say that those who, by the cultivation of the medical art, expended their industry in our behalf were only raving? What shall we say of the mathematical sciences? Shall we deem them to be the dreams of madmen? Nay, we cannot read the writings of the ancients on these subjects without the highest admiration; an admiration which their excellence will not allow us to withhold. But shall we deem anything to be noble and praiseworthy, without tracing it to the hand of God? Far from us be such ingratitude; an ingratitude not chargeable even on heathen poets, who acknowledged that philosophy and laws, and all useful arts were the inventions of the gods. Therefore, since it is manifest that men whom the Scriptures term carnal, are so acute and clear-sighted in the investigation of inferior things, their example should teach us how many gifts the Lord has left in possession of human nature, notwithstanding of its having been despoiled of the true good.

In contemplating Calvin’s thoughts, I appreciated his thoughts on common grace, a divine endowment bestowed upon every individual created in the image of God. It speaks to the inherent ability of each person to manifest intelligence in various domains and, remarkably, to discern truth in the world. What becomes evident is that even those who may not attribute their insights to the divine source possess the capacity to grasp elements of truth.

I realize the the early Puritans and others are held up as great thinkers. However, although I have a college degree and read much from different sources, I admit I have a very difficult time reading their sermons and writings.. Lots of generalizations and flowing big terms which really don’t give down to earth practical concepts in the important area of “try to learn what is pleasing to the Lord.” I wonder who exactly were the types of people who would be in the Sunday services to hear these sermons? I can’t imagine simple farming folk, just struggling day to day to make a living could ever relate to this style of preaching and writing. Perhaps the Puritans only had the upper class, educated folk in the church, but still the structure of the language and word choice maybe flowing and wonderful sounding, but not down to earth. I am currently trying to read and comprehend writings of John Owen, but I find the writings of James in his New Testament book very practical. Yes, I listen to John Piper, but have the same problem with his sermons, and he does in fact hold the Puritans in very high regard.

LikeLike