Most people know that the Dead Sea as a salty lake sitting at the lowest point below sea level. And they’re right, though there’s much more to it. The Dead Sea is not just salty; it’s a massive, hypersaline lake that today stretches 31 miles long and 9 miles wide, nestled in a closed drainage basin between Jordan and Israel. To put its saltiness into perspective, the Dead Sea contains 300 to 350 PPT (parts per thousand) salts, compared to a mere 35 PPT (parts per thousand) for typical seawater (Oren, 2010). This extreme salinity creates a unique environment that has intrigued people for millennia.

The Dead Sea represents the final destination for all its tributaries, including its largest source of new water, the Jordan River. This closed system, where water flows in but doesn’t flow out, has created the conditions for the dramatic changes we’ve witnessed over time and continue to observe today.

The Water Balance Puzzle

The first people to set their eyes upon the Dead Sea may have wondered about its water sources and sinks. Some ancient thinkers, such as the Greek philosopher Thales of Miletus (648-546 BCE), believed the earth rested on water and that springs and even rivers had their sources from below (O’Grady, 2017). Following this logic, the Dead Sea could have been connected to a vast subterranean sea, explaining its changing volume.

Today, we understand that the water balance of the Dead Sea differently. The waters of the Dead Sea don’t drain away underground; they simply evaporate. This process, combined with the input from its tributaries, creates a delicate balance that has been dramatically altered in recent times.

From the earliest recorded observations, it was evident that this lake doesn’t maintain a near constant shoreline like the Mediterranean Sea. The Dead Sea’s shoreline fluctuates significantly, with noticeable changes occurring even on an annual basis. These fluctuations result from two primary factors: the input volume from the Jordan River and the rate of evaporation (Yechieli et al., 1998).

Historical Water Level Changes

Over the last century, we’ve observed a profound shift in the Dead Sea’s water balance, with evaporation consistently exceeding the input of new water. The result has been a dramatic shrinking of this ancient lake.

To put this decline into perspective, let’s look at some historical measurements:

- In 1930, the surface of the Dead Sea was about 1,280 feet (390 meters) below sea level.

- By 2014, its surface had dropped more than 120 feet (37 meters) lower.

- Most of this water loss occurred in just the two decades preceding 2014.

- In the decade leading up to 2014, the lake was dropping at a rate of about three feet per year.

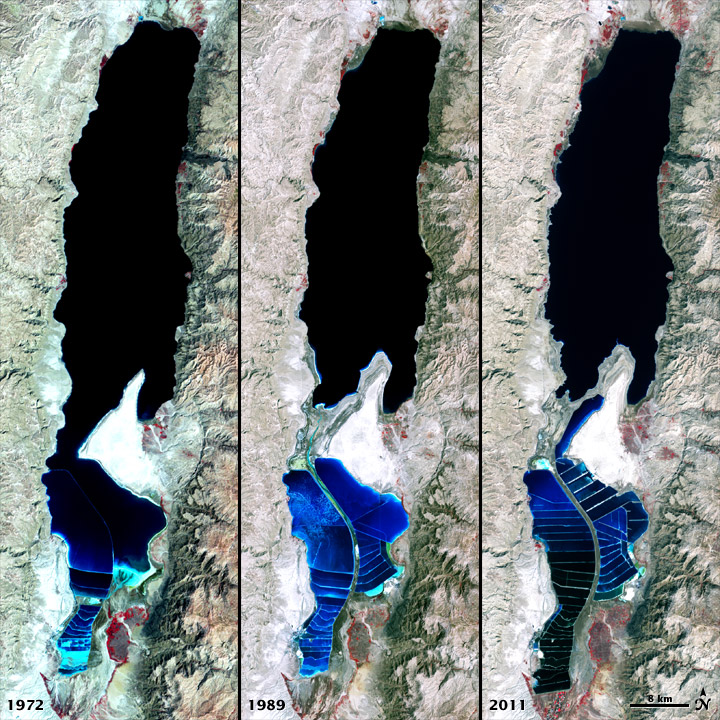

However, recent data paints an even more alarming picture. As of 2021, the surface of the Dead Sea stood at approximately -435 meters below sea level, indicating that the rate of decline has not slowed. In fact, between 1972 and 2019, the Dead Sea’s surface area decreased by about 33%, shrinking from approximately 1000 km² to 670 km². Even more concerning, they found that the rate of decline has accelerated in recent years, with the water level dropping by an average of 1.24 meters per year from 2017 to 2019.

This rapid decline is transforming the landscape around the Dead Sea at an unprecedented rate. Resorts built along the shore in the mid-20th century now stand hundreds of feet above and thousands of feet away from the current waterline. The retreating shoreline is not just a matter of inconvenience for tourists; it represents a fundamental shift in this unique ecosystem and poses significant challenges for the region’s environment and economy (Ionescu et al., 2012).

Causes of Rapid Decline

The dramatic shrinkage of the Dead Sea is not a natural phenomenon but largely the result of human activities. Like the Colorado River that is sucked dry by agricultural and urban sprawl before it reaches the Pacific Ocean, the Jordan River is almost entirely depleted by a thirsty population before it reaches the Dead Sea. The diversion of water from the Jordan River for agriculture and domestic use has significantly reduced the inflow to the Dead Sea. Approximately 95% of the Jordan River’s natural flow is now diverted by Israel, Syria, and Jordan (Gleick, 2014). This leaves just a small stream to feed the Dead Sea, starving it of its primary water supply.

In addition to reduced input from the Jordan River, the shrinking of the Dead Sea can also be attributed to several other factors. The arid climate of the region leads to consistently high evaporation rates, which remain constant even as water input decreases (Lensky et al., 2005). Large-scale mineral extraction operations on both the Israeli and Jordanian shores, particularly for potash and bromine, contribute significantly to water loss through the use of extensive evaporation ponds (Rawashdeh et al., 2013). While not the primary cause, climate change may exacerbate the situation by potentially increasing evaporation rates and reducing precipitation in the region.

This combination of factors has created a severe imbalance in the Dead Sea’s water budget, leading to its rapid and continuing decline.

Environmental and Economic Impacts

The consequences of the Dead Sea’s decline are far-reaching and ever-changing, with shoreline retreat and sinkhole formation being the most significant issues. The retreating shoreline has left resorts built in the mid-20th century stranded far from the current waterline, posing challenges for the tourism industry and complicating future development plans (Khlaifat et al., 2010). Even more dangerous is the proliferation of sinkholes, caused by fresh ground water dissolving underground salt layers causing the collapse of the material above. As of 2021, over 6,000 sinkholes have formed around the Dead Sea, up from just 40 in the 1990s (Yechieli et al., 2016). These sinkholes, some reaching depths of 25 meters or more, pose significant risks to infrastructure, agriculture, and human safety, making large areas unsafe for human activity and adding an element of constant risk to life in the region. The unpredictable nature of these changes affects both economic development and daily life for local communities, underlining the urgent need for sustainable management of this unique ecosystem.

Future Projections

Owing to the large changes in the regions observed in the past 50 years, the future of the Dead Sea is a subject of intense scientific study and growing concern. Despite being the lowest place on Earth, the Dead Sea waters themselves reach a depth of almost 1000 feet. At its current rate of decline, some early estimates suggested that the lake could completely dry out in less than 500 years (Niemi, 1997). However, this simplistic projection doesn’t account for several complicating factors.

As the Dead Sea shrinks, its salinity increases, which in turn slows down the rate of evaporation. This feedback mechanism suggests that complete desiccation is unlikely under natural conditions. Recent hydrological modeling by Yechieli et al. (2016) takes into account factors such as changing evaporation rates, groundwater inflow, and basin morphology. Their results indicate that while significant drops in lake level are possible during prolonged dry periods, complete desiccation of the Dead Sea is improbable due to continuous groundwater inflow.

However, these models also highlight the precarious state of the Dead Sea’s water balance. Even small changes in climate or human water use patterns could have significant impacts on the lake’s future. The projected effects of climate change in the region, including increased temperatures and potentially decreased precipitation, add another layer of uncertainty to these predictions.

Historical Perspective on Dead Sea Levels

While the current decline of the Dead Sea is alarming, it’s important to place these changes within the context of the lake’s long geological history. And it’s that history that we have the most interest. There is abundant evidence that the Dead Sea has experienced dramatically different water levels over time.

At one extreme, geological studies have revealed that the sea nearly dried up completely in the distant past. Torfstein et al. (2015) analyzed halite sequences in the Dead Sea Deep Drilling Project (DSDDP) core and identified two major dry periods during the last interglacial, around 147-140 ka and 137-128 ka. During these periods, the lake level dropped by up to 130 feet below its current elevation. We will look further at the evidence of much lower levels of the Dead Sea in the past in Part IV of this series.

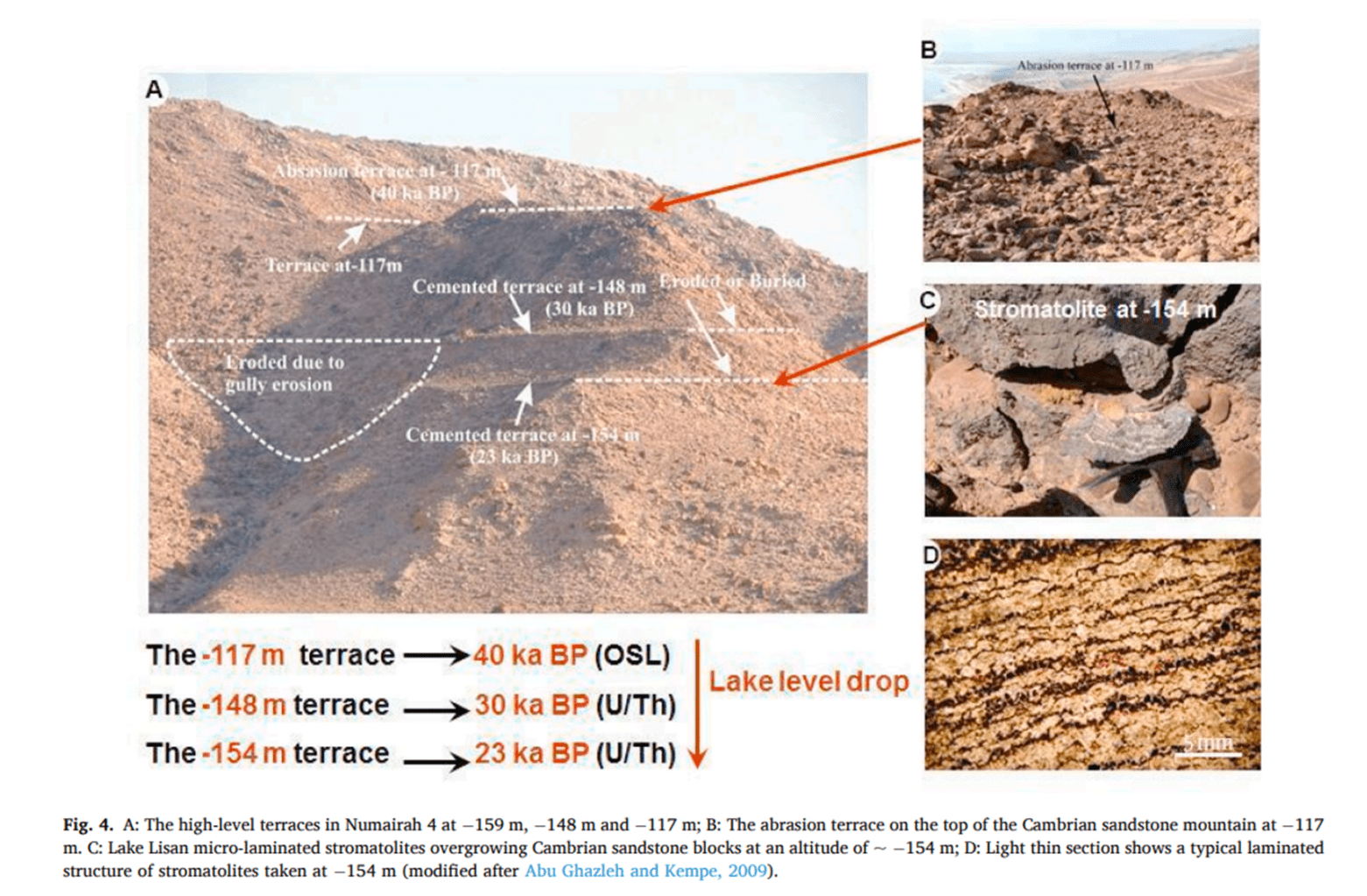

Yet the Dead Sea has also seen far higher water levels than we see today. Geological evidence indicates that during the Last Glacial Maximum (about 20,000 years ago), the Jordan Valley was the site of Lake Lisan, a water body that combined the Dead Sea and Sea of Galilee into one massive lake (Bartov et al., 2002) some 124 miles long or 4 times its present length of 31 miles. At its peak, Lake Lisan stood more than 700 feet higher than the modern Dead Sea.

Ancient shorelines, still visible today hundreds of feet above the current water level, provide physical evidence of these past high stands. Many studies of these previous shorelines have been performed. For example, Lisker et al. (2009) used U-Th dating of shore deposits to reconstruct a detailed history of lake level changes, identifying multiple high stands throughout the late Pleistocene.

More recently, Palchan et al. (2019) used a combination of sedimentological and geochemical proxies to identify a previously unknown low stand during the early Holocene, around 10-8.5 ka BP. This period coincides with the ‘8.2 ka event’, a global cooling episode, suggesting a complex relationship between global climate and Dead Sea levels. For example, there is a distinct change in inputs to ancient bogs in my home state of Ohio (Lutz et al., 2007).

These dramatic fluctuations raise questions about the timescale and conditions under which such changes occurred. How long did it take for the Dead Sea to nearly dry up? How quickly did it fill to form Lake Lisan? And what were the climatic conditions that drove these changes?

Understanding these past fluctuations is crucial for several reasons. First, it provides context for the current decline, helping us understand whether the present situation is unprecedented or part of a long-term pattern. Second, it offers insights into how the Dead Sea ecosystem has responded to past climate changes, which could inform predictions about its future resilience. Finally, these long-term records provide valuable data for climate scientists studying global climate patterns over geological timescales.

However, it is the questions of the past not of the future of the Dead Sea but of how the geological evidence intersects with the historical record, particularly as documented in biblical texts, and what this tells us about the more recent history of the Dead Sea that we are most interested. For example, how should a reader of the scriptures react to the evidence of dramatic changes in Dead Sea lake level fluctuations? Before we can answer that question, we need to examine what we can learn about the Dead Sea from the biblical authors.

The Dead Sea in Biblical Context

The Dead Sea has a long history in recorded human history, especially in the Bible. It is referenced in Scripture from early in Genesis all the way through the Gospels of the New Testament. This record allows us to establish some clear constraints on the timeline of the Dead Sea’s evolution within the context of recorded human history.

The first significant biblical reference to the Dead Sea area comes in Genesis 13, when Abraham and Lot survey the Jordan Valley. The text describes a well-watered plain, “like the garden of the Lord, like the land of Egypt” (Genesis 13:10, NIV). This description suggests that around 4100 years ago, the Dead Sea and its surroundings were not dramatically different from what we see today in terms of general layout, though perhaps with somewhat more abundant water (Frumkin and Elitzur, 2002).

Furthermore, the Bible provides no indication that since the time of Abraham, the Dead Sea has grown or shrunk radically in recorded history. This consistency of the climatological and ecological environment in the biblical record suggests that any major changes in the Dead Sea’s size or level must have occurred prior to the events described in Genesis 13.

Deuteronomy 3:17, we see another description of the land’s boundaries that mentions the Dead Sea. The verse reads, “the Arabah also, with the Jordan as the border, from Chinnereth as far as the Sea of the Arabah, the Salt Sea, under the slopes of Pisgah on the east.” This passage is part of Moses’ recounting of the lands that God had given to the Israelites. Once again, the Dead Sea serves as a significant geographical marker, helping to define the eastern border of the Promised Land.

Similarly, Numbers 34:3 it’s called the “Salt Sea,” a name that vividly captures its most distinctive feature. The verse reads, “Your south side shall be from the wilderness of Zin alongside Edom, and your southern border shall run from the end of the Salt Sea on the east.” Like the Numbers passage, this passage is part of God’s instructions to Moses regarding the boundaries of the Promised Land.

Joshua 3:16, which recounts the miraculous crossing of the Jordan River. The verse tells us, “The waters coming down from above stood and rose up in a heap very far away, at Adam, the city that is beside Zarethan, and those flowing down toward the Sea of the Arabah, the Salt Sea, were completely cut off. And the people passed over opposite Jericho.” Here, the Dead Sea is referred to as both the “Sea of the Arabah” and the “Salt Sea.” This passage not only mentions the Dead Sea but also highlights its connection to the Jordan River, which feeds into it. The stopping of the Jordan’s flow would have had a direct impact on the water levels of the Dead Sea, emphasizing the interconnectedness of these water bodies in the region’s hydrology.

Finally, in Joshua 12:3, we find another reference to the Dead Sea in the context of Israel’s conquest of the land. The verse states, “and the Arabah to the Sea of Chinneroth eastward, and in the direction of Beth-jeshimoth, to the Sea of the Arabah, the Salt Sea, southward to the foot of the slopes of Pisgah.” Here, the Dead Sea is again called both the “Sea of the Arabah” and the “Salt Sea.” This passage uses the Dead Sea as a geographical reference point, helping to define the extent of the conquered territories. It’s interesting to note how the biblical authors used well-known landmarks like the Dead Sea to orient their readers and provide a clear picture of the land’s geography.

In all these references, we see the Dead Sea consistently referred to as the “Salt Sea” or the “Sea of the Arabah.” The Hebrew terms used (Strongs H4417 & H3220 for Salt Sea, and H6160 for Arabah) emphasize both its saline nature and its location in the desert region known as the Arabah. These biblical descriptions align remarkably well with what we know about the Dead Sea today – a hypersaline lake located in a desert valley.

What’s particularly striking about these biblical references is how they portray the Dead Sea as a constant, unchanging feature of the landscape. Whether describing borders, recounting miracles, or detailing conquests, the biblical authors consistently use the Dead Sea as a fixed point of reference. This suggests that, at least within the timeframe of these biblical accounts, the Dead Sea’s general characteristics and location remained stable – a fact that aligns well with our geological understanding of the region’s relatively recent past.

If the Dead Sea nearly dried up in the past, or if it was part of a much larger lake system, these events must have happened before the time of Abraham. Similarly, the formation of the high shorelines we see today, hundreds of feet above the current lake level effectively filling the entire rift valley from below the Dead Sea to above the present-day Sea of Galilee, must also predate biblical times as there is no place to fit a massive lake system in the Genesis narrative nor any time after that.

At this point you may be asking yourself, what about Noah’s Flood? Surely this could account for at least the higher lake levels in the pre-Abrahamic times. We will keep this in mind as we continue to look more closely at some of the geological features of the Dead Sea rift.

The Dead Sea as a Scientific and Historical Record Keeper

The Dead Sea serves as both a scientific archive of Earth’s history and a corroborating source for biblical narratives. Its sediments and surrounding geology provide a wealth of information about past climates, tectonic activity, and environmental conditions in the region.

Geological evidence from the Dead Sea basin offers strong support for viewing this as an ancient place. The thick sequences of sediments, multiple cycles of drying and filling, and the time required for the formation of features like Mt. Sedom (a massive salt diapir which we will look at in detail later) are difficult to reconcile with a young Earth interpretation (Bartov et al., 2002; Torfstein et al., 2015).

At the same time, the geological record doesn’t contradict the biblical narrative, setting aside the question of the Noahic flood account for now, but rather provides a broader context for it. The stability of the Dead Sea’s general configuration over the past 4000 years, as suggested by both geological and biblical records, speaks to the reliability of the biblical account as a historical document.

Moreover, the Dead Sea’s sediments serve as an important climate archive. The alternating layers of salt, mud, and evaporites provide a high-resolution record of past climate changes. Recent studies have used this record to reconstruct regional climate patterns over hundreds of thousands of years, offering valuable insights into long-term climate variability (Neugebauer et al., 2014).

Conclusion

The Dead Sea, Earth’s lowest lake, is a unique natural laboratory that continues to yield fascinating insights into our planet’s past and present. From its dramatic water level fluctuations to its role in human history, the Dead Sea has a story to tell us.

Current research paints a concerning picture of the Dead Sea’s immediate future. The rapid decline in water levels, driven primarily by human activities, poses significant environmental and economic challenges. The proliferation of sinkholes, the retreat of shorelines, and the potential for further ecosystem disruption all underscore the urgency of addressing this issue.

Yet, when viewed through the lens of geological time, we see that the Dead Sea has undergone even more dramatic changes in the past. These ancient fluctuations, driven by natural climate variations, provide important context for understanding the current situation and potential future scenarios.

In the coming parts of this series, we will look deeper into the geological processes that shaped the Dead Sea, explore the cutting-edge research techniques being used to study it, and consider the implications of this research for our understanding of Earth’s history before we turn our attention to how we might interpret this evidence in light of models of understanding earth’s history based on the Bible.

Next up: Dead Sea Chronicles Part III: The Jordan Valley – A Land Literally Ripped Apart

References:

Bartov, Y., Stein, M., Enzel, Y., Agnon, A., & Reches, Z. (2002). Lake levels and sequence stratigraphy of Lake Lisan, the late Pleistocene precursor of the Dead Sea. Quaternary Research, 57(1), 9-21.

Gleick, P. H. (2014). Water, drought, climate change, and conflict in Syria. Weather, Climate, and Society, 6(3), 331-340.

Ionescu, D., Siebert, C., Polerecky, L., Munwes, Y. Y., Lott, C., Häusler, S., … & De Beer, D. (2012). Microbial and chemical characterization of underwater fresh water springs in the Dead Sea. PloS one, 7(6), e38319.

Frumkin, A., & Elitzur, Y. (2002). Historic Dead Sea level fluctuations calibrated with geological and archaeological evidence. Quaternary Research, 57(3), 334-342.

Khlaifat, A., Hogan, M., Phillips, G., Nawayseh, K., Amira, J., & Talafeha, E. (2010). Long-term monitoring of the Dead Sea level and brine physico-chemical parameters “from 1987 to 2008”. Journal of Marine Systems, 81(3), 207-212.

Lensky, N. G., Dvorkin, Y., Lyakhovsky, V., Gertman, I., & Gavrieli, I. (2005). Water, salt, and energy balances of the Dead Sea. Water Resources Research, 41(12).

Lisker, S., Vaks, A., Bar-Matthews, M., Porat, R., & Frumkin, A. (2009). Stromatolites in caves of the Dead Sea Fault Escarpment: implications to latest Pleistocene lake levels and tectonic subsidence. Quaternary Science Reviews, 28(1-2), 80-92.

Lutz, B., Wiles, G., Lowell, T., & Michaels, J. (2007). The 8.2-ka abrupt climate change event in Brown’s Lake, northeast Ohio. Quaternary Research, 67(2), 292-296.

Niemi, T. M., Ben-Avraham, Z., & Gat, J. (Eds.). (1997). The Dead Sea: the lake and its setting (No. 36). Oxford University Press.

Neugebauer, I., Brauer, A., Schwab, M. J., Waldmann, N. D., Enzel, Y., Kitagawa, H., … & DSDDP Scientific Party. (2014). Lithology of the long sediment record recovered by the ICDP Dead Sea Deep Drilling Project (DSDDP). Quaternary Science Reviews, 102, 149-165.

O’grady, P. F. (2017). Thales of Miletus: the beginnings of western science and philosophy. Routledge.

Oren, A. (2010). The dying Dead Sea: The microbiology of an increasingly extreme environment. Lakes & Reservoirs: Research & Management, 15(3), 215-222.

Palchan, D., Erel, Y., & Stein, M. (2019). Mobilization of fine detritus to the Dead Sea Basin during the late glacial and early Holocene. Quaternary Science Reviews, 218, 395-405.

Al Rawashdeh, S., Ruzouq, R., Al-Fugara, A. K., Pradhan, B., Ziad, S. A. H., & Ghayda, A. R. (2013). Monitoring of Dead Sea water surface variation using multi-temporal satellite data and GIS. Arabian Journal of Geosciences, 6, 3241-3248.

Shafir, H., & Alpert, P. (2011). Regional and local climatic effects on the Dead-Sea evaporation. Climatic Change, 105(3), 455-468.

Torfstein, A., Goldstein, S. L., Kushnir, Y., Enzel, Y., Haug, G., & Stein, M. (2015). Dead Sea drawdown and monsoonal impacts in the Levant during the last interglacial. Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 412, 235-244.

Yechieli, Y., Gavrieli, I., Berkowitz, B., & Ronen, D. (1998). Will the Dead Sea die? Geology, 26(8), 755-758.

Yechieli, Y., Abelson, M., & Baer, G. (2016). Sinkhole formation and subsidence along the Dead Sea coast, Israel. Hydrogeology Journal, 24(3), 601.

Yechieli, Y., Abelson, M., Bein, A., Crouvi, O., & Shtivelman, V. (2006). Sinkhole “swarms” along the Dead Sea coast: reflection of disturbance of lake and adjacent groundwater systems. Geological Society of America Bulletin, 118(9-10), 1075-1087.