Imagine standing on the shores of an ancient lake, its waters lapping at your feet some 80,000 years ago. This isn’t just any lake – it’s Lake Lisan, the massive predecessor to today’s Dead Sea we learned about in Part IV. Now, fast forward to the present day. You’re standing in the same spot, but the water’s edge is nowhere in sight. Instead, you’re perched high above the current Dead Sea, surrounded by rocky outcrops that hold a secret: the story of this vanished lake.

How do we know what this spot looked like in the past and how far in the past? Stromatolites – layered, rock-like structures formed by ancient microorganisms. These stone chronometers have stood watch over the changing landscape for tens of thousands of years, preserving a record of Lake Lisan’s rise and fall.

Stromatolites might not look like much at first glance. They’re often mistaken for ordinary rocks or mineral deposits. But to geologists, they’re treasure troves of information. Formed by cyanobacteria—a photosynthetic bacteria—in shallow waters, stromatolites grow layer by layer, trapping sediment and precipitating minerals as they go. This process creates a distinct laminated (layered) structure that not only tells us where the water’s edge once was, but also provides a means to date these ancient shorelines (Kempe and Kazmierczak, 2007).

And this is why we are interested in these unassuming grey rocks. We are interested in the history and origins of the Dead Sea basin and these rocks help us reconstruct that history.

The Hunt for High-Level Stromatolites

When you’re searching for evidence of ancient shorelines, sometimes you have to look up – way up. That’s exactly what researchers like Abu Ghazleh and Kempe (2021) did in their quest to understand the history of Lake Lisan.

Their investigation began with a detailed examination of aerial photos of the eastern coast of the Dead Sea. They were looking for areas where high-level terraces – potential ancient shorelines – might be well preserved. But finding these features was just the first step. To truly understand their significance, the team needed precise measurements of their elevations.

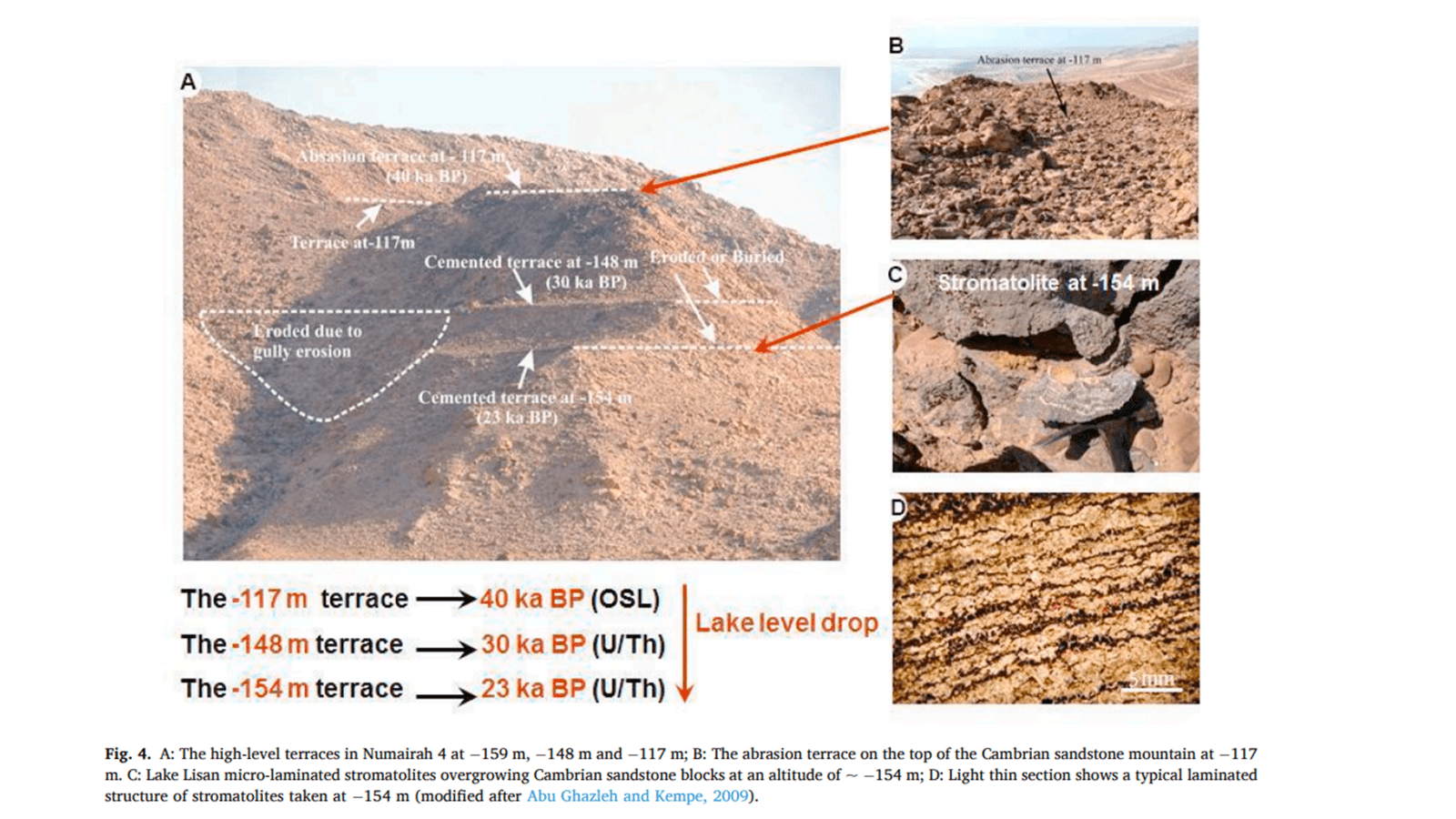

The tool they used was differential GPS (DGPS). This high-tech surveying tool allowed the researchers to measure the altitude of these terraces with incredible precision – we’re talking less than a centimeter of error (Abu Ghazleh and Kempe, 2021). They surveyed six cross-sections along the eastern shore of the Dead Sea, carefully documenting the location and height of each terrace.

But the biggest discovery came when they started exploring caves and shallow rock shelters along these ancient shorelines. Here, protected from erosion, they found an especially useful predictor of past climates and lake levels: stromatolites. These delicate structures, formed by ancient microorganisms in the shallow waters of Lake Lisan, had been preserved for tens of thousands of years.

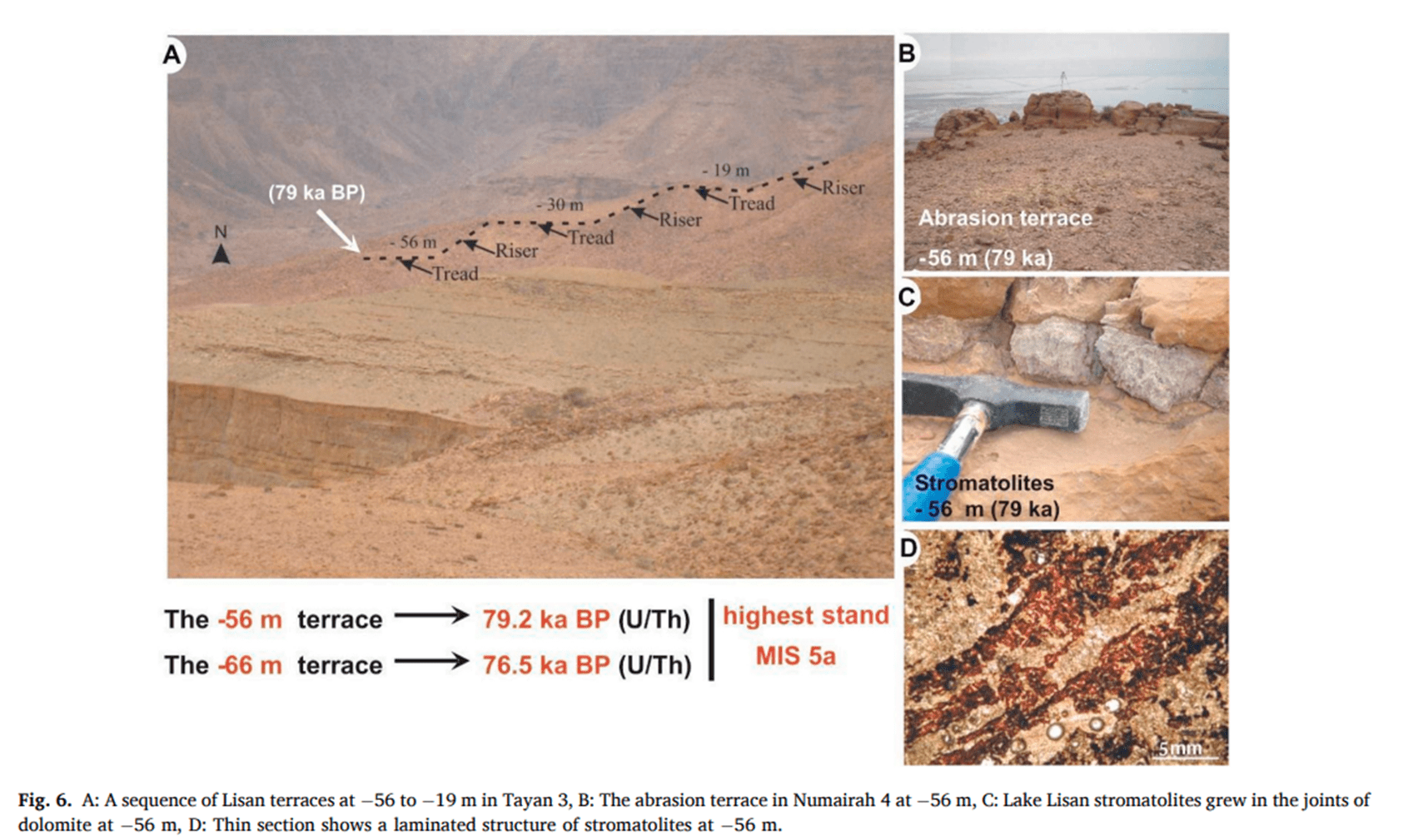

The discoveries were exciting. They found stromatolites at elevations ranging from 1043 feet to 617 feet (310 to -188 meters) below sea level (Lisker et al., 2009). But the real surprise came when Abu Ghazleh and Kempe (2021) discovered stromatolites at just 183 feet (56 meters) below sea level – that’s more than 1200 feet (370 meters) above the current Dead Sea level!

To put this in perspective, imagine the Empire State Building. Now imagine it completely submerged. That’s roughly the difference between the current Dead Sea level and where they found these ancient lake deposits.

But the discoveries didn’t stop there. They found a series of terraces stretching even higher, up to present-day sea level. While these highest terraces didn’t have the classic stromatolite formations, they did have thin, red crusts with a micro-laminated texture similar to the lower stromatolites. This suggests that Lake Lisan may have reached even greater heights than previously thought.

These findings are important for our understanding of the history of the Dead Sea and Jordan Valley. The presence of these high terraces and stromatolites raise questions. How old are these high-level stromatolites? What do they tell us about past climate?

What Stromatolites Tell Us About Ancient Lake Levels

Stromatolites are like nature’s bathtub rings. Just as the ring around your tub marks the highest water level, stromatolites mark ancient shorelines. But they’re much more than simple water level indicators – they’re time capsules preserving a wealth of information about past environments.

First and foremost, stromatolites tell us where the water’s edge once was. These structures only form in shallow, sunlit waters, typically no more than a few meters deep. So when we find stromatolites high up on the shores of the Dead Sea basin, we know that the water level must have been at least that high (Lisker et al., 2009).

The discoveries made by Abu Ghazleh and Kempe (2021) and others have revealed multiple high stands of Lake Lisan. They found stromatolites at various elevations, including 617, 505, and 450 feet (188 m, -154 m, -137 m), and most surprisingly, at 183 feet (56 m) above sea level. Each of these levels represents a period when the lake stood at that height long enough for stromatolites to form.

These latest findings provide a new perspective on the extent of Lake Lisan. Previous estimates put Lake Lisan’s maximum level at around 617 feet (180 m) below sea level (Bartov et al., 2002). The discovery of stromatolites at 188 feet (56 m) blows this estimate out of the water (pun intended). It suggests that Lake Lisan stood at least 326 feet (100 m) higher than previously thought.

But what does this mean for our understanding of past climate in the region? In a word: water. Lots of it. For Lake Lisan to reach these extreme heights, there must have been significantly more precipitation in the region than there is today. We’re talking about a climate wet enough to fill a basin over 1300 feet (400 m) deeper than it is now, in an area that’s currently one of the most arid on Earth.

These high lake levels align with what climate scientists call Marine Isotope Stage 5a (MIS 5a), a period of relatively warm climate between about 85,000 to 80,000 years ago. During this time, increased rainfall in the Eastern Mediterranean region led to the expansion of lakes across the Levant (Torfstein et al., 2015).

But the stromatolites tell us more than just how high the water got. Their very existence at these elevations suggests that the lake maintained these high levels for extended periods. Stromatolites don’t form overnight – they require stable conditions to grow. This implies that these wet periods weren’t just brief spikes, but sustained climatic episodes lasting hundreds or even thousands of years.

Moreover, the presence of stromatolites at multiple levels indicates that Lake Lisan didn’t simply fill up once and then recede. Instead, it underwent multiple cycles of rising and falling, each leaving behind its own set of stromatolite “bathtub rings”.

These findings have implications for our understanding of past climate variability in the region. They suggest that the Eastern Mediterranean has experienced dramatic swings between wet and dry periods over the past 100,000 years. This kind of long-term perspective is crucial for understanding natural climate variability and contextualizing current and future climate change.

Dating the Dead Sea’s Stone Sentinels

When it comes to unraveling the history of Lake Lisan, knowing the “where” of ancient shorelines is only half the battle. The other crucial piece of the puzzle is the “when”. This is where the science of geochronology comes into play, allowing us to turn these stone sentinels into a detailed timeline of the lake’s past.

Researchers have employed a variety of dating methods to determine the age of Lake Lisan stromatolites. The most prominent of these is uranium-thorium (U/Th) dating. This method is particularly useful for carbonate materials like stromatolites and can provide dates going back several hundred thousand years (Kaufman et al., 1998).

Here’s how it works in a nutshell: Uranium, which is soluble in water, gets incorporated into the stromatolite as it forms. Over time, this uranium decays into thorium at a known rate. By measuring the ratio of uranium to thorium in a sample, scientists can calculate how long ago the stromatolite formed.

But U/Th dating isn’t the only tool in the geochronologist’s toolkit. Researchers have also used radiocarbon (14C) dating for younger samples and optically stimulated luminescence (OSL) dating for associated sediments (Abu Ghazleh and Kempe, 2021). Each of these methods has its strengths and limitations, and using multiple techniques allows scientists to cross-check their results and build a more robust chronology.

Dating stromatolites does come with its challenges, though. One major issue is contamination. Stromatolites can incorporate older or younger material as they form, which can skew the results. Scientists have to carefully clean and prepare their samples to minimize this risk. They also need to correct for the presence of detrital thorium – thorium that was incorporated into the stromatolite when it formed, rather than being produced by radioactive decay (Haase-Schramm et al., 2004).

Despite these challenges, the results of dating efforts have been remarkable. Abu Ghazleh and Kempe (2021) found that the highest stromatolites, at 188 feet below sea level, dated to between 79,200 ± 3,300 and 76,500 ± 5,600 years ago. This places the highest stand of Lake Lisan squarely in Marine Isotope Stage 5a, a period of relatively warm climate, as determined by previously by a set of independent data, in the last glacial cycle.

But that’s not the whole story. Their dating efforts revealed a complex history of lake level fluctuations. After its highest stand around 80,000 years ago, Lake Lisan appears to have dropped dramatically, reaching -1148 feet (-350 m) by about 63,600 years ago. The lake then rose again, reaching above 450 feet (-137) m by about 32,000 years ago, before experiencing several more cycles of rise and fall.

These dates align well with other records of climate change from the region and beyond. For example, some of the lake level drops correspond with Heinrich events – periods of extreme cold in the North Atlantic that affected climate patterns worldwide (Bartov et al., 2003).

The power of these dating efforts lies not just in individual dates, but in the overall picture they paint. They reveal Lake Lisan as a dynamic system, responding to regional and global climate changes over tens of thousands of years. This long-term perspective is crucial for understanding the natural variability of climate in the region and for putting current changes into context.

Moreover, these dates pose a significant challenge to young-Earth creationist interpretations of the Dead Sea’s history. The stromatolite record spans a period of over 60,000 years – far longer than the approximately 4,350 years since Noah’s Flood in young-Earth timelines. And that’s not even considering the time needed for the Dead Sea basin to form in the first place.

Mineral Composition of Stromatolites

The mineral composition of stromatolites serves as a window into the past chemistry of Lake Lisan, offering valuable insights into how the lake’s environment changed over time. By analyzing the minerals present in stromatolites from different elevations and ages, researchers can infer changes in water chemistry, salinity, and even climate conditions.

One of the key mineral indicators in Lake Lisan stromatolites is the ratio of aragonite to calcite. Both are calcium carbonate minerals, but they form under different conditions. Aragonite typically precipitates in more saline waters with higher Mg/Ca ratios while calcite tends to form in fresher waters with lower Mg/Ca ratios.

Abu Ghazleh and Kempe (2021) found that stromatolites from the highest elevations (0 to -56 m above sea level) were composed primarily of calcite. This suggests that during the periods of highest lake levels, around 80,000 years ago, Lake Lisan was relatively fresh. The dominance of calcite implies a significant influx of freshwater, likely due to increased precipitation in the region.

As you move down to lower elevations, representing later periods in the lake’s history, the mineral composition shifts. Stromatolites from middle elevations (-249 to -384 feet) show a mix of calcite and aragonite, indicating fluctuating conditions with periods of higher salinity. At the lowest levels (-1150 feet), stromatolites are composed almost entirely of aragonite, suggesting a hypersaline environment similar to today’s Dead Sea.

This mineral sequence tells a story of Lake Lisan’s evolution. An initial freshwater phase during its highest stand followed by a transition period with fluctuating salinity and finally a hypersaline phase as the lake shrank towards its current state.

Beyond just aragonite and calcite, the presence or absence of other minerals can provide additional clues. For example: gypsum (calcium sulfate) in some layers indicates periods of extreme evaporation and the presence of dolomite (calcium magnesium carbonate) in some samples might suggest times of higher magnesium concentrations in the lake.

Researchers also analyze the Mg/Ca ratios within the carbonate minerals themselves. Higher Mg/Ca ratios in calcite, for instance, indicate more saline conditions during formation.

It’s worth noting that interpreting mineral compositions isn’t always straightforward. Post-depositional alterations can sometimes change the original mineral structure. However, the dry climate of the Dead Sea region has helped preserve many of these stromatolites in their original state, making them particularly valuable for paleoenvironmental reconstructions.

The mineral composition of Lake Lisan stromatolites provides a detailed record of the lake’s chemical evolution. This information, combined with dating methods and other proxies, allows researchers to reconstruct a nuanced history of climate change and hydrological conditions in the Dead Sea basin over tens of thousands of years.

Beyond Stromatolites: Other Evidence from Ancient Shorelines

Let’s quickly review and expand a bit on some other evidence to help us paint a picture of this ancient lake’s history, some of which we explored in Part IV (Lake Lisan).

A clearly visible remnant of ancient lake shores are wave-cut terraces. These are basically nature’s version of steps carved into the landscape by the relentless action of waves. Imagine the lake level staying put for a while, giving waves time to erode a flat platform into the shoreline. Then the lake drops quickly, and you’ve got a terrace marking where the water once stood.

Abu Ghazleh and Kempe (2009) found dozens and dozens of these terraces along the southeastern coast of the Dead Sea, ranging from -750 feet all the way up to -62 feet above sea level. Each one of these terraces represents a period when the lake level was stable enough for waves to do their carving work.

What is critical for our questions of origins is that these terraces line up nicely with the elevations where stromatolites were found. It’s like having two independent witnesses corroborating the same story. For example, they found a prominent terrace at -485 feet that matches up with stromatolites dated to about 30,500 years ago.

In addition to wave-cut terraces there are often associated beach deposits. These are exactly what they sound like – the sand, gravel, and other sediments you’d expect to find on a beach. But in this case, we’re finding them high and dry, far above the current Dead Sea level (Bartov et al. 2002).

Bowman (1971) described deposits of well-sorted sand and gravel at elevations up to -590 feet above sea level. These deposits often show characteristic beach features like cross-bedding (layers at an angle to the main bedding) and ripple marks. What’s particularly significant about these beach deposits is that they can sometimes contain datable materials. Organic matter like shells or plant remains can be radiocarbon dated, giving us another way to pin down when the lake was at different levels.

All of these features – the wave-cut terraces, the beach deposits, and our stromatolites – work together to tell a consistent story. They all point to Lake Lisan having stood at much higher levels in the past, fluctuating dramatically over tens of thousands of years.

You might wonder though, why don’t we find these features at all elevations? Why do we see clusters of evidence at certain levels? This pattern suggests that the lake didn’t just gradually rise and fall. Instead, it seems to have had periods of relative stability punctuated by more rapid changes. That’s a clue about past climate patterns that helps scientists describe the history of this region.

Growth Rates and the Young-Earth Creationist Timeline

If you’re firmly in the young-Earth camp, this section, like many other parts of our series on the origins of the Dead Sea, might make you a bit uncomfortable. But stick with me, because these stromatolites and beach deposits are observations from the world that God made and are telling us a story.

First, let’s think about those stromatolites. How long does it take for stromatolites to form? Well, it’s not exactly a quick process. Modern stromatolites, like those found in Shark Bay, Australia, grow at rates of about 0.3-0.4 mm per year (Reid et al., 2000). That’s slower than your fingernails grow! Now, conditions in ancient Lake Lisan might have been different, but we’re still talking about a very gradual process.

Here’s where things get interesting. The stromatolites found at various levels around the Dead Sea basin show evidence of multiple cycles of growth and lake level changes. We’re not just looking at one continuous growth period, but rather several distinct phases of stromatolite formation, interrupted by times when the lake level dropped and growth stopped.

Let’s put some numbers to this. Abu Ghazleh and Kempe (2021) found stromatolites at elevations ranging from -1150 feet to -185 feet above sea level. U-Th dating of these stromatolites revealed ages spanning from about 80,000 to 19,000 years ago. That’s over 60,000 years of lake level fluctuations recorded in these rocky layers!

Now, here’s where the young-Earth creationist timeline runs into a real time crunch. If we accept the idea that the Earth is only about 6,000 years old, with Noah’s Flood occurring around 4,350 years ago, we’d have to squeeze all of these lake level changes and multiple phases of stromatolite growth into a very short timeframe. We’re talking about fitting dozens of meters of vertical lake level change, plus the time needed for stromatolites to grow at each level, into just a few thousand years at most.

The stromatolites aren’t the only evidence we need to consider. The Dead Sea basin also contains thick layers of salt and sediment that would have taken considerable time to accumulate. For example, the Sedom Formation, which underlies the Lisan Formation, is up to 2.5 miles (4 km) thick in places (Zak, 1967). That’s a lot of sediment including many precipitated salts to pile up in a short time!

The young-earth proponent is obligated to suggest that the Flood could have created these features rapidly. For example, in a 2010 article on the Answers in Genesis website, Andrew Snelling suggested that “the Ice Age that followed the Flood” could explain many of the features we see around the Dead Sea. While not identifying any particular feature that this Ice Age was responsible for, he is was likely thinking that a post-Flood ice age could have rapidly filled and drained lakes, creating shorelines at various levels.

However, this interpretation faces significant challenges. For one, it doesn’t explain the multiple cycles of lake level changes we see recorded in the stromatolites and other features. It also doesn’t account for the time needed for stromatolites to grow at each level. Remember, modern stromatolites grow very slowly – less than half a millimeter per year!

So why do the multiple lines of evidence support an old Earth interpretation? Let’s review some of the features and methods for determining age:

- Multiple cycles: The stromatolites and shoreline features show evidence of multiple cycles of lake level changes, which are difficult to squeeze into a young-Earth timeframe.

- Correlation with global climate events: The lake level changes align well with known global climate events over tens of thousands of years.

- Radiometric dating: U-Th dating of the stromatolites provides ages up to about 80,000 years, far beyond the young-Earth timeframe.

- Slow growth rates: The time needed for stromatolites to grow at each level is difficult to reconcile with a rapid, post-Flood scenario.

- Tectonics: The evidence for long-term tectonic subsidence in the basin fits better with an old-Earth timeline.

I think it’s important to consider all the evidence and how well different interpretations explain what we see. An old-Earth interpretation currently provides the most comprehensive explanation for the diverse evidence we find around the Dead Sea.

So, the young-earth creationist is left with a conundrum. Either these stromatolites grew much, much faster in the past than anything we observe today (and we’d need a mechanism to explain that), or we need to reconsider the timeline. I think it’s important to wrestle with this evidence and consider what it might mean for our understanding of Earth’s history. These crusty old stromatolites, wave-cut terraces and preserved beach material are a piece of nature’s history book, and they’ve got quite a tale to tell – if we’re willing to listen.

References:

Abu Ghazleh, S., & Kempe, S. (2009). Geomorphology of Lake Lisan terraces along the eastern coast of the Dead Sea, Jordan. Geomorphology, 108(3-4), 246-263.

Abu Ghazleh, S., & Kempe, S. (2021). Discovery of high-level terraces of Last Glacial Lake Lisan (Dead Sea) and Eastern Mediterranean paleoclimatic implications. Quaternary International, 604, 38-50.

Bartov, Y., Goldstein, S. L., Stein, M., & Enzel, Y. (2003). Catastrophic arid episodes in the Eastern Mediterranean linked with the North Atlantic Heinrich events. Geology, 31(5), 439-442.

Bartov, Y., Stein, M., Enzel, Y., Agnon, A., & Reches, Z. (2002). Lake levels and sequence stratigraphy of Lake Lisan, the late Pleistocene precursor of the Dead Sea. Quaternary Research, 57(1), 9-21.

Bowman, D. (1971). Geomorphology of the shore terraces of the late Pleistocene Lisan Lake (Israel). Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 9(3), 183-209.

Haase-Schramm, A., Goldstein, S. L., & Stein, M. (2004). U-Th dating of Lake Lisan (late Pleistocene dead sea) aragonite and implications for glacial east Mediterranean climate change. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 68(5), 985-1005.

Kaufman, A., Wasserburg, G. J., Porcelli, D., Bar-Matthews, M., Ayalon, A., & Halicz, L. (1998). U-Th isotope systematics from the Soreq cave, Israel and climatic correlations. Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 156(3-4), 141-155.

Kempe, S., & Kazmierczak, J. (2007). Hydrochemical key to the genesis of calcareous nonlaminated and laminated cyanobacterial microbialites. In Algae and Cyanobacteria in Extreme Environments (pp. 241-264). Springer, Dordrecht.

Lisker, S., Vaks, A., Bar-Matthews, M., Porat, R., & Frumkin, A. (2009). Stromatolites in caves of the Dead Sea Fault Escarpment: implications to latest Pleistocene lake levels and tectonic subsidence. Quaternary Science Reviews, 28(1-2), 80-92.

Reid, R. P., Visscher, P. T., Decho, A. W., Stolz, J. F., Bebout, B. M., Dupraz, C., … & DesMarais, D. J. (2000). The role of microbes in accretion, lamination and early lithification of modern marine stromatolites. Nature, 406(6799), 989-992.

Snelling, A. A. (2010). The Geology of Israel within the Biblical Creation-Flood Framework of History: 2. The Flood Rocks. Answers Research Journal, 3, 267-309.

Torfstein, A., Goldstein, S. L., Kushnir, Y., Enzel, Y., Haug, G., & Stein, M. (2015). Dead Sea drawdown and monsoonal impacts in the Levant during the last interglacial. Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 412, 235-244.

Zak, I. (1967). The geology of Mount Sedom [Ph. D. thesis]: Hebrew University, Jerusalem, 208 p.(in Hebrew with English abstract).