As we conclude our journey through the geological wonders of the Dead Sea region, I find myself amazed by the intricate story written in stone, salt, and sediment. Over the course of this series, we’ve explored a landscape shaped by tectonic forces, climatic shifts, and the relentless power of water and erosion. From the formation of the Dead Sea rift, the ancient Lake Lisan, the seismic history recorded in sediments, and to the towering salt pillar of Mount Sodom, each of these features tells a story.

Yet, as a Christian committed to the truth and authority of Scripture, I’m acutely aware that for many believers, this geological evidence presents a challenging dilemma. How do we reconcile the apparent antiquity of the Earth with traditional interpretations of Genesis? Is there truly a conflict between the “book of nature” and the “book of Scripture”?

These are not merely academic questions. They touch on fundamental issues of faith, our understanding of God’s character, and how we interpret the world around us. I’ve witnessed firsthand how debates over the age of the Earth and the interpretation of Genesis have caused division within the church, sometimes even tearing families and congregations apart.

It’s with this weight of responsibility that I approach this final chapter, seeking to offer a perspective that honors both the integrity of Scripture and the evidence God has left for us in His creation.

Affirming My Christian Faith and Commitment to Scripture

Before we dive into the specifics, I want to affirm unequivocally that I am a Christian who believes in the inspiration and inerrancy of Scripture. I stand with the Apostle’s Creed and affirm the central tenets of the Christian faith: the Trinity, the incarnation, death, and resurrection of Jesus Christ, and salvation by grace through faith. My exploration of science, including the geological evidence we’ve examined in this series, is motivated by a desire to better understand the world God has made and to glorify Him through that understanding.

I believe in the inerrancy of the Bible as it pertains to the message God intends to convey. However, this doesn’t mean that every passage must be interpreted literally or that our interpretations of Scripture are inerrant. That said, we must approach the Bible with humility, recognizing that our understanding can be shaped by our cultural context, preconceptions, and limited knowledge.

It’s crucial to emphasize that accepting the scientific evidence for an old Earth does not require abandoning biblical authority or inerrancy. Rather, it invites us to carefully consider how we interpret Scripture, especially in passages that touch on the natural world. As St. Augustine wisely cautioned:

“Usually, even a non-Christian knows something about the earth, the heavens, and the other elements of this world, about the motion and orbit of the stars and even their size and relative positions, about the predictable eclipses of the sun and moon, the cycles of the years and the seasons, about the kinds of animals, shrubs, stones, and so forth, and this knowledge he holds to as being certain from reason and experience. Now, it is a disgraceful and dangerous thing for an infidel to hear a Christian, presumably giving the meaning of Holy Scripture, talking nonsense on these topics; and we should take all means to prevent such an embarrassing situation, in which people show up vast ignorance in a Christian and laugh it to scorn.” (Augustine, The Literal Meaning of Genesis)

Similarly, when we think about what God has chosen to communicate to us through the biblical authors we need to be cognizant of trying to have scriptures answer the questions we, especially in our modern world, we may wish or demand that they answer. Lefebvre (2019) observes with respect to the early chapters of Genesis that:

“Those who come to this text looking for scientific origins will find many question unanswered. There is no information about the origins of the angels or of demons in this chapter. There is no information about the origins of bacteria, of the introduction of weather patterns, or even the presence of rivers in the world. There is no information about black holes or dark energy or galaxies. There is no hint concerning the vast size of the universe: the entire worldview of the Genesis creation account fits within the dome of the earth, with the heavenly lights suspended from that dome in the sky.” (LeFebvre Pg. 183)

With this spirit of intellectual honesty and faith seeking understanding, let’s examine where the geological evidence from the Dead Sea aligns with Scripture, and how we might approach areas of apparent conflict.

Where There Is No Conflict

As we’ve explored the Dead Sea region, one of the most striking realizations has been how well the geological evidence aligns with the biblical accounts for the past 4,000 to 5,000 years. All of the eyewitness reports of the Dead Sea in the Bible describe features of the Dead Sea and Jordan Valley that are consistent with what we observe today and what the geological evidence indicates was present in the past.

For instance, when Abraham and Lot looked out over the Jordan Valley (Genesis 13:10), they saw a well-watered plain that would have been recognizable to us today. The Bible’s descriptions of the Dead Sea’s salinity, the presence of asphalt pits, and the overall geography of the region are remarkably accurate when compared to both modern observations and geological records.

Archaeological evidence from sites around the Dead Sea, such as Qumran (home of the Dead Sea Scrolls), corroborates the biblical accounts of human habitation and activity in the region during historical times (Magness, 2002). The seismic history recorded in the Dead Sea sediments, as we explored earlier in this series, aligns well with earthquakes mentioned in the Bible and other historical sources (Kagan et al., 2011).

Moreover, other ancient historical references support the consistency of the Dead Sea’s features over time. Aristotle in the 4th century BC referred to the Dead Sea’s high salinity and buoyancy. Diodorus Siculus, Strabo, and Pliny the Elder all provided descriptions of the Dead Sea between the 1st century BC and the 1st century AD that closely match both biblical accounts and modern observations (Nissenbaum, 1993). These historical references support the idea that the climate and geographical features of the region have remained relatively stable over the past several millennia.

The alignment between Scripture and geological evidence for this recent period is significant. It demonstrates that the Bible provides accurate historical and geographical information, which should give us confidence in its reliability. At the same time, it shows that careful scientific study can corroborate and enhance our understanding of biblical narratives.

However, as we’ve seen throughout this series, the geological evidence also points to a much longer history for the Dead Sea and its surroundings – a history spanning hundreds of thousands, even millions of years. It’s this deep history that presents the greatest challenge to traditional young-earth interpretations of Genesis.

Addressing the Perceived Conflict: Age of the Earth and Noah’s Flood

For many Christians, particularly those who hold to a young-earth creationist (YEC) perspective, the geological evidence we’ve examined throughout this series presents a significant challenge. The idea that the Earth, and by extension the Dead Sea region, could be millions of years old contradicts their understanding of Genesis and the timeline they’ve derived from biblical genealogies.

The root of this conflict often lies in two key areas: the interpretation of the creation account in Genesis 1 and the extent and impact of Noah’s Flood. Young-earth creationists believe that the only consistent interpretation of scriptures necessitates that the Earth was created in six literal 24-hour days around 6,000 years ago, and that Noah’s Flood was a global catastrophe that reshaped the entire planet about 4,500 years ago.

However, after 30 years of studying both the Bible and God’s creation, conversing with both old and young earth advocates with orthodox Christian backgrounds, I’ve come to understand that this young-earth interpretation is not the way to faithfully read the intent of the authors of Scripture. In fact, I believe that insisting on a young earth creates unnecessary conflicts not only with science but also with the biblical text itself.

As we’ve seen throughout this series, the geological evidence from the Dead Sea region points to a much older earth and a complex history that doesn’t align with a recent global flood. The Dead Sea rift itself, formed by tectonic processes, shows evidence of millions of years of movement (Garfunkel and Ben-Avraham, 1996). The sediments in the basin, including the salt deposits of Mount Sodom, speak to long periods of deposition and evaporation cycles (Torfstein et al., 2009). The seismic history recorded in the lake sediments extends back over 220,000 years (Kagan et al., 2018).

To compress all of this into a few thousand years requires us to assume that either the evidence is being massively misinterpreted by virtually all geologists (including nearly all Christians working in geology professions), or that God created the Earth with an appearance of age that doesn’t reflect reality. Neither of these options are satisfactory to me, both scientifically and theologically.

Interpreting the Flood Narrative

If you have ever pondered how we should understand the story of Noah’s Flood? You’re not alone. As someone deeply invested in bridging science and faith, I’ve found the insights of scholars like John Walton, Tremper Longman III, G.K. Beale, and Richard Middleton particularly helpful. While they each bring unique perspectives to the table, they all are conservative Christians committed to understanding the text in its original context and as part of the larger narrative of Scripture.

Dr. John Walton, for instance, argues that we need to read Genesis through the lens of its original audience. He suggests that the Flood narrative uses “rhetorical hyperbole,” a common feature in ancient Near Eastern literature, to emphasize the theological significance of the event rather than to provide a scientifically precise description. He also argues that the emphasis is not on the physical mechanics of the Flood, but on its theological significance as an “un-creation” event. Walton suggests that the Flood narrative is more about God re-ordering the cosmos and re-establishing order from chaos, rather than primarily being about physical destruction and rebuilding (Walton, 2015).

Dr. Tremper Longman III proposes that the flood account uses “global language” to describe a local event. He points out that the Bible often uses universal or “global” language to describe events that were likely more geographically limited. This use of expansive language to describe significant events was common in ancient Near Eastern literature (Longman, 2005).

Dr. G.K. Beale, known for his temple theology, interprets the Flood narrative as a de-creation and re-creation event that mirrors the original creation account. He sees it as part of God’s ongoing temple-building project in creation (Beale, 2011). Furthermore, his work on biblical theology has helped me see the Flood narrative as part of a larger pattern of God’s judgment and re-creation throughout Scripture (Beale, 2011). This theological reading maintains the profound spiritual significance of the Flood without requiring it to be a worldwide catastrophe that reshaped the planet’s geology.

Dr. Richard Middleton sees the Flood as a critical moment in God’s project of partnering with humanity to cultivate the earth. He emphasizes the covenant established with Noah as a renewal and expansion of the original human vocation. Middleton’s approach considers the Flood narrative’s place in the larger biblical story and its ethical implications for today (Middleton, 2005).

These scholars, among others, help us see that the Flood narrative is not primarily about judging the historicity of a global deluge, but about understanding its theological significance within the story of God’s dealings with humanity and creation. They show us how we can take the text seriously without requiring it to be a scientific account of earth history.

Understanding the use of phenomenological and hyperbolic language in Scripture is crucial when interpreting passages like the Flood narrative in Genesis. The Bible often describes events and phenomena as they appear to the observer, using language that conveys the experience rather than precise scientific description. This is evident in phrases like “the sun stood still” (Joshua 10:13) or references to “the four corners of the earth” (Isaiah 11:12). Similarly, Scripture frequently employs hyperbole to emphasize theological points, as seen in Joshua’s account of subduing “the whole region” (Joshua 10:40) or the claim that “the whole world sought audience with Solomon” (1 Kings 10:24).

This use of language extends to the Flood narrative and appears throughout the Bible. For instance, when Paul states that the gospel “has been proclaimed to every creature under heaven” (Colossians 1:23), we understand this as rhetorical exaggeration emphasizing the gospel’s wide reach, not a literal claim that every single creature had heard the message. Recognizing these linguistic features helps us interpret the Flood account more accurately, understanding that the author may have been using expansive language to convey the totality of God’s judgment and the completeness of the destruction within the scope of the narrator’s world, rather than providing a scientifically precise description of a global event.

The account of Joseph’s famine in Genesis 41 provides another striking example of hyperbolic language in Scripture that directly relates to how we understand the Flood narrative. Verses 56 and 57 state that “the famine had spread over all the land (erets)” and that “all the earth (erets) came to Egypt to Joseph to buy grain, because the famine was severe over all the earth (erets).” The Hebrew word ‘erets’ is used here to describe both ‘land’ and ‘earth’, highlighting the fluid nature of its usage. While a surface or literal reading of our English text might suggest a truly global famine, historical and archaeological evidence doesn’t support a worldwide food shortage at this time. Instead, this language emphasizes the severity and widespread impact of the famine within the known world of the author and original audience. The phrase “all the earth came to Egypt” is particularly telling – it’s clearly not meant to be taken literally, as it’s implausible that every person on the planet traveled to Egypt. This mirrors the use of similar language in the Creation account and Noah’s Flood narrative, where phrases like “the face of the earth” are employed. Understanding this use of expansive, hyperbolic language helps us interpret these passages more accurately, recognizing the author’s intent to convey the extensive and severe nature of these events, rather than providing a scientifically precise, global description.

Even Jesus employs such language. In His reference to the Queen of Sheba provides another example of this biblical use of language. In Matthew 12:42, Jesus states that the “Queen of the South… came from the ends of the earth to listen to Solomon’s wisdom.” Here, “the ends of the earth” is clearly not meant literally – we know the kingdom of Sheba was likely located in modern-day Yemen or Ethiopia, not at the physical extremity of the planet. Rather, this phrase represents the limits of the known world to Jesus’ audience. It emphasizes the great distance the Queen traveled, underlining her dedication to seeking wisdom. This usage demonstrates how biblical authors often employed the worldview and geographical understanding of their time to convey meaning, rather than adhering to what we now know to be scientifically or geographically accurate. Recognizing this helps us understand how similar language in the Flood narrative might be interpreted – not as a statement about literal global geography, but as a way of expressing the extensive nature of the event in terms the original audience would understand.

Understanding the Flood narrative in this way allows us to appreciate its theological message without requiring a global catastrophe that conflicts with geological evidence. It preserves the historical basis of the event while recognizing that its description may use the rhetorical conventions of its time and culture.

The genre of the text, the chiastic structure emphasizing a theological purpose to the text, the use of hyperbolic language and the lack of any physical evidence of such a flood provide a good reason to believe that a literal global flood was in the mind Moses or whoever the authors of the Pentateuch may have been. Was there a flood? Yes, Moses recounts a flood to make a theological point. His audience may or may not have been aware of said flood but would not have understood the description in such literal terms even while they would have accepted that it was based on a real event.

I also am of the mind to view the Flood event from the perspective of Covenant Theology. By that I mean that “all” is speaking of God’s chosen people at the time, the descendants of Seth. Cain’s descendants were outside Eden and effectively in the wasteland which is already a symbol of destruction/disorder. There was no need to destroy them with a flood. But the Sethites turned from God and Noah alone was faithful. Just like when God allowed the Israelites to die before entering the land. The other peoples of the world are not his immediate concern hence the need for a literal global flood was not necessary. Yet the salvific message of Noah still has universal implications because the covenant has been brought to the gentiles and so members of all nations can be grafted into his own.

So much more could be said. Solid theological resources can be found in Sailhamer’s “The Meaning of the Pentateuch”, Tremper Longman’s book “How to Read Genesis” and even G.K. Beal’s book “A New Testament Biblical Theology” provides a great overview of the OT from a Biblical Theology perspective which I have found very helpful.

Emphasizing Historical Diversity of Christian Interpretation

A second focal point in appreciating how Scripture may align with deep geological timescales is to recognize the historical range of Christian interpretations. Far from modern debates alone, early theologians showed significant openness toward figurative or less time-bound readings of Genesis. Origen (3rd c.), for instance, saw the opening chapters of Genesis as rich in symbolic meaning, cautioning believers not to confine their understanding to a strictly literal framework (Origen 1936, II.). Several centuries later, Augustine (4th–5th c.) similarly warned against “rash interpretations” of Genesis 1 that would pit scriptural teaching against reason and experience, suggesting instead that the days could represent “God-divided epochs” rather than precise 24-hour periods (Augustine 1990).

In the Reformation era, John Calvin remarked that Moses wrote in language comprehensible to everyday people rather than in technical scientific terms. Calvin recognized that the scriptural text’s aim is to depict God’s sovereign role in creation rather than to map every geophysical mechanism in detail (Calvin 2009). Collectively, these varied stances underscore that even within a robustly orthodox tradition, faithful interpreters have long held differing views on how Genesis articulates time. Such perspectives encourage us to regard geologic or archaeological insights about the Dead Sea and its ancient sedimentary layers as neither alien nor hostile to scriptural claims. Instead, they can be seen as part of the “good gifts” of creation waiting to be studied in concert with biblical truth.

Theological Implications of an Ancient Earth

Accepting the geological evidence for an ancient earth doesn’t diminish the theological significance of Scripture. In fact, I believe it enhances our understanding of God’s creation and His patient, long-term work in the world.

An old earth perspective allows us to marvel at the intricate processes God has used to shape our planet over vast periods of time. The gradual formation of the Dead Sea rift, the cycles of climate change recorded in its sediments, the slow accumulation of salt to form Mount Sodom – all these speak to a God who works not just in sudden miracles, but in slow, steady processes over immense timescales.

Moreover, an ancient Earth actually provides a stronger foundation for understanding God’s redemptive plan. The long ages of Earth’s history showcase God’s patient work in preparing a world that could sustain human life and, ultimately, be the stage for the incarnation, death, and resurrection of Christ.

This view also aligns well with other Scriptural themes. The Bible often portrays God as patient and long-suffering (2 Peter 3:8-9). An old earth demonstrates God’s patience on a cosmic scale. It also resonates with the scriptural theme of progressive revelation – the idea that God has gradually revealed more of Himself and His plan over time. In John 5:17, Jesus says, “My Father is always at his work to this very day, and I too am working.” An old Earth showcases God’s continuous involvement in creation, rather than a single week of creative activity followed by mere preservation. And as the psalmist wrote, “The heavens declare the glory of God; the skies proclaim the work of his hands” (Psalm 19:1). The more we learn about the age and complexity of creation, the more we can echo this praise.

Some worry that accepting an old earth undermines key Christian doctrines like original sin or the gospel. However, I’ve found that these doctrines don’t depend on a young earth. The theological truth of human sinfulness and need for redemption stands regardless of when the first humans appeared. The gospel – God’s plan to redeem humanity through Christ – remains powerful whether that plan was set in motion 6,000 or 13.8 billion years ago.

In fact, an old earth perspective can deepen our appreciation for the scope of God’s redemptive plan. If God has been patiently working in creation for billions of years, how much more amazing is it that He would enter into that creation in the person of Jesus Christ to redeem it? Christ’s work of redemption is just as necessary and powerful whether creation is young or old. In fact, seeing the vast scope of cosmic history can enhance our appreciation for God’s plan of redemption set in motion “before the creation of the world” (Ephesians 1:4).

Ultimately, I believe that embracing the evidence for an ancient Earth can deepen our faith and broaden our understanding of God’s works. It calls us to approach Scripture with humility, recognizing that our interpretations may need to be revised as we learn more about the world God has made. As John Calvin wrote, “If we regard the Spirit of God as the sole fountain of truth, we shall neither reject the truth itself, nor despise it wherever it shall appear, unless we wish to dishonor the Spirit of God” (Institutes of the Christian Religion, 1.7.4).

Engaging with Other Christian Perspectives

As we grapple with these complex issues of science and faith, it’s crucial to recognize that many respected Christian scholars and leaders have wrestled with these same questions and come to accept an old Earth view while maintaining a high view of Scripture. Their work can provide valuable insights and reassurance for those struggling to reconcile scientific evidence with their faith.

For instance, B.B. Warfield, the prominent Princeton theologian known for his robust defense of biblical inerrancy, saw no conflict between evolutionary science and Christian orthodoxy. He wrote, “I do not think that there is any general statement in the Bible or any part of the account of creation, either as given in Genesis 1 and 2 or elsewhere alluded to, that need be opposed to evolution” (Noll and Livingstone, 2000).

Organizations like BioLogos, founded by Collins, provide extensive resources for Christians seeking to understand how evolutionary creation aligns with biblical faith. The American Scientific Affiliation, a fellowship of Christians in science, has also been a forum for thoughtful engagement with these issues for decades.

For those wanting to delve deeper into these topics, I recommend the following resources:

Science and Faith (Mostly Origins Questions)

Books

Reformed Theology and Evolutionary Theory by Gijsbert Van den Brink (2020)

Kingdom Prologue: Genesis Foundations for a Covenantal Worldview by Merideth Kline

Ancient Near Eastern Thought and the Old Testament by John Walton (2006)

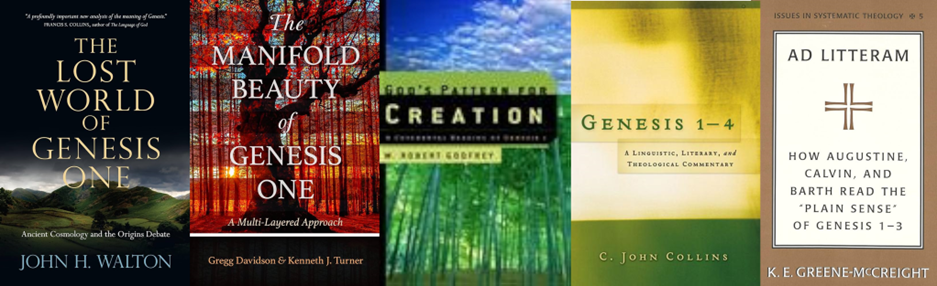

The Manifold Beauty of Genesis One: A Multi-Layered Approach by Gregg Davidson and Kenneth Turner (2021)

Genesis 1-4: A linguistic, literary and theological commentary by C. John Collins (2006)

God’s Pattern for Creation: a covenantal reading of Genesis 1 by W. Robert Godfrey (2003)

The Lost World of Genesis One: Ancient Cosmology and the Origins Debate by John Walton (2009)

Did Adam and Eve Really Exist?: Who They Were and Why You Should Care by C. John Collins (2011)

The Art of Biblical History by V. Philips Long (1994)

Ad Litteram: How Augustine, Calvin and Barth read the ‘plain sense’ of Genesis 1-3 by K. E. Greene-McCreight (1999)

The Creationists: the evolution of scientific creationism by Ronald Numbers (1992)

The Pentateuch as Narrative – A Biblical-Theological Narrative by John Sailhamer (1995)

The Meaning of the Pentateuch: Revelation, Composition and Interpretation by John Sailhamer (2009)

The Temple and the Church’s Mission: A Biblical Theology of the Dwelling Place of God by G. K. Beale (2004)

A New Testament Biblical Theology: The Unfolding of the Old Testament in the New by G. K. Beale (2011)

Scholarly and popular articles

The Garden Temple by G.K. Beale (JETS 2005)

Scandal of the Evangelical Mind: A Biblical and Scientific Critique of Young-Earth Creationism by Bruce Gordon (Science, Religion and Culture, 2014)

THE CREATION Intelligently Designed or Optimally Equipped? by Howard Van Till (Theology Today)

Evangelicals, Creation, and Scripture: An Overview by Mark Noll (BioLogos)

Nuts and Bolts of Creation by George Murphy (PSCF 2005)

Reading Genesis by Roy Clouser (PSCF 2016)

Because it had Rained: A Study of Gen 2:5-7 with Implications for Gen 2:4-25 and Gen 1:1-2:3 by Mark Futato (WTJ 1998)

These books and scholarly articles offer in-depth explorations of how we can maintain biblical fidelity while accepting the scientific evidence for an old Earth.

The Harmony of Science and Faith

Throughout this series on the Dead Sea, we’ve seen how scientific investigation can reveal the intricate workings of God’s creation. Far from threatening faith, I believe that scientific discovery can deepen our appreciation for the complexity and beauty of the world God has made.

The apostle Paul wrote that “since the creation of the world God’s invisible qualities—his eternal power and divine nature—have been clearly seen, being understood from what has been made” (Romans 1:20). Science, at its best, is a way of studying “what has been made.” When we approach it with humility and wonder, it can lead us to a greater appreciation of God’s wisdom and power.

This perspective requires intellectual honesty. We must be willing to follow the evidence where it leads, even if it challenges our preconceptions. But we can do this with the confidence that all truth is God’s truth. As Augustine said, “Let every good and true Christian understand that wherever truth may be found, it belongs to his Master” (Augustine, On Christian Doctrine).

This harmony between science and faith isn’t a modern invention. Many of the pioneers of modern science, from Galileo to Kepler to Newton, saw their scientific work as a way of understanding God’s creation. In the words of Johannes Kepler, “The chief aim of all investigations of the external world should be to discover the rational order and harmony which has been imposed on it by God and which He revealed to us in the language of mathematics” (Koestler, 1959).

Conclusion

As we conclude our exploration of the Dead Sea’s deep history, we’ve seen how the geological evidence aligns beautifully with the biblical accounts of the region’s more recent past. We’ve also grappled with how this evidence challenges some traditional interpretations of Earth’s age and history.

The Dead Sea, with its layers of sediment recording climatic changes, its salt formations speaking to long periods of evaporation, and its fault lines testifying to millions of years of tectonic movement, stands as a testament to the age and complexity of God’s creation. At the same time, its waters and shores have been witness to much of the history recorded in Scripture.

I believe that embracing both the geological and biblical evidence allows us to gain a fuller picture of God’s work in the world. It invites us to marvel at the patient, long-term processes through which God has shaped our planet, while also appreciating His intimate involvement in human history as recorded in Scripture.

For those who may still struggle with these ideas, I encourage you to continue exploring. Engage with the scientific evidence, study the Scriptures deeply, and be open to new understandings. Remember that faith and reason are not enemies, but allies in our quest to understand God and His creation.

As we close this series, I’m reminded of the words of the psalmist: “Great are the works of the Lord; they are pondered by all who delight in them” (Psalm 111:2). The Dead Sea, with all its geological wonders and historical significance, is indeed one of the Lord’s great works. In the end, whether you agree with every conclusion I’ve drawn or not, I hope this series has deepened your appreciation for the complexity of God’s creation and the richness of His word. May it inspire you to continue seeking understanding, always remembering that in Christ, “all things hold together” (Colossians 1:17, NIV) – including science and faith.

References:

Augustine. (415). The Literal Meaning of Genesis.

Augustine. On Christian Doctrine.

Augustine. (1982). The Literal Meaning of Genesis (J. H. Taylor, Trans.). Newman Press.

Beale, G. K. (2011). A New Testament Biblical Theology: The Unfolding of the Old Testament in the New. Baker Academic.

Calvin, John. Commentaries on the First Book of Moses Called Genesis. Translated by John King. Bellingham, WA: Logos Bible Software, 2009.

Collins, F. S. (2006). The Language of God: A Scientist Presents Evidence for Belief. Free Press.

Diodorus Siculus. (1st century BCE). Bibliotheca Historica.

Garfunkel, Z., & Ben-Avraham, Z. (1996). The structure of the Dead Sea basin. Tectonophysics, 266(1-4), 155-176.

Kagan, E. J., Stein, M., & Marco, S. (2018). Integrated paleoseismic chronology of the last glacial Lake Lisan: From lake margin seismites to deep-lake mass transport deposits. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth, 123(4), 2806-2824.

Kepler, J. (1619). Harmonices Mundi (The Harmony of the World).

LeFebvre, M. (2019). The Liturgy of Creation: Understanding Calendars in Old Testament Context. Intervarsity Press.

Longman III, T. (2005). How to Read Genesis. InterVarsity Press.

McGrath, A. E. (2009). A Fine-Tuned Universe: The Quest for God in Science and Theology. Westminster John Knox Press.

Nissenbaum, A. (1993). The Dead Sea – An Economic Resource for 10,000 Years. Hydrobiologia, 267(1-3), 127-141.

Origen. On First Principles. Translated by G. W. Butterworth. Gloucester, MA: Peter Smith, 1936.

Pliny the Elder. (1st century CE). Natural History.

Ross, H. (2018). Navigating Genesis: A Scientist’s Journey through Genesis 1-11. Reasons to Believe.

Strabo. (1st century CE). Geography.

Torfstein, A., Gavrieli, I., Katz, A., Kolodny, Y., & Stein, M. (2009). Gypsum as a monitor of the paleo-limnological-hydrological conditions in Lake Lisan and the Dead Sea. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 73(14), 4452-4468.

Walton, J. H. (2009). The Lost World of Genesis One: Ancient Cosmology and the Origins Debate. IVP Academic.

Walton, J. H. (2015). The Lost World of Adam and Eve: Genesis 2-3 and the Human Origins Debate. IVP Academic.

Young, D. A., & Stearley, R. F. (2008). The Bible, Rocks and Time: Geological Evidence for the Age of the Earth. IVP Academic.