The Dead Sea, as we’ve explored in previous installments, is a remarkable archive of Earth’s history. But beyond recording climate changes and lake level fluctuations, this unique body of water also holds within its sediments a detailed record of seismic activity in the region. This seismic history not only provides crucial information for understanding the area’s geological past but also intersects with human history and even biblical narratives.

In this part of our series, we’ll examine the earthquake history recorded in the Dead Sea sediments. We’ll explore how geologists decipher this record, what it tells us about the region’s tectonic activity, and how it might relate to historical events – including the destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah described in the Book of Genesis and a number of other earthquakes recorded in the Old and New Testaments.

Understanding Seismites: The Geological Record of Earthquakes

Before we dive into the specific seismic history of the Dead Sea, it’s crucial to understand how earthquakes leave their mark in sedimentary records. The key lies in structures known as seismites, which serve as geological time capsules, preserving evidence of ancient earthquakes.

Seismites are sedimentary features formed by earthquake-induced deformation of soft, water-saturated sediments. In the context of lake sediments like those in the Dead Sea, seismites often appear as disrupted or contorted layers sandwiched between undisturbed, horizontal strata (Agnon et al., 2006). These structures provide a unique window into the seismic past, allowing geologists to reconstruct earthquake histories spanning thousands of years.

The formation of seismites is a process that illustrates the dynamic nature of sediments during seismic events. When an earthquake strikes, it sends seismic waves through the Earth. In water-saturated sediments, these waves can cause a phenomenon known as temporary liquefaction. During liquefaction, the sediment momentarily loses its strength and behaves more like a fluid than a solid. This transformation can lead to various types of deformation:

- Soft-sediment deformation structures: These include ball-and-pillow structures, flame structures, and load casts. In ball-and-pillow structures, denser sediment sinks into less dense layers below, creating rounded, pillow-like shapes. Flame structures appear as tongue-like projections of less dense sediment pushed upward into denser layers. Load casts occur when a denser layer sinks into a less dense layer, creating irregular, lobe-like structures.

- Mixed layers: Intense shaking can completely homogenize previously distinct sediment layers. This mixing erases the original stratification, creating a uniform layer that stands out from the undisturbed sediments above and below.

- Brecciated layers: In some cases, partially lithified (hardened) sediment can be broken up into angular fragments suspended in a matrix of liquefied sediment. This creates a distinctive “broken” appearance in the sedimentary record.

- Injection structures: Liquefied sediment can be forced upwards through overlying layers, forming dykes (vertical intrusions) or sills (horizontal intrusions). These structures often cut across existing bedding planes, providing clear evidence of post-depositional deformation.

In the Dead Sea, one of the most common types of seismites is the “mixed layer,” where distinct annual laminations are disrupted and homogenized over a certain thickness (Kagan et al., 2018). These mixed layers are particularly valuable for paleoseismologists because they can be easily identified and dated, providing a clear record of past seismic events.

The study of seismites in the Dead Sea has been greatly advanced by the use of high-resolution imaging techniques. For example, X-ray fluorescence (XRF) scanning allows researchers to analyze the elemental composition of sediment cores at sub-millimeter scales, revealing subtle changes in sediment composition that may indicate seismic disturbance (Neugebauer et al., 2014). Similarly, magnetic susceptibility measurements can highlight changes in sediment source or grain size that may be associated with seismic events.

It’s important to note that not all disturbed sediment layers are seismites. Similar structures can be caused by other processes, such as underwater landslides, rapid changes in sedimentation, or even bioturbation (disturbance by living organisms). This is where the expertise of geologists comes in, using various criteria to distinguish true seismites from other deformation structures. These criteria may include the lateral extent of the deformed layer, its relationship to known fault lines, and the presence of specific deformation features characteristic of seismic shaking.

The Dead Sea is particularly well-suited for preserving seismites due to several factors:

- Hypersaline waters: The extreme salinity of the Dead Sea prevents most life forms from surviving, thus minimizing bioturbation that could obscure seismite structures.

- Rapid sedimentation: The Dead Sea basin experiences high rates of sediment accumulation, which helps to quickly bury and preserve seismites.

- Tectonic setting: The Dead Sea sits along the active Dead Sea Transform fault, ensuring a steady supply of seismic events to create seismites.

- Varved sediments: The Dead Sea’s annually laminated (varved) sediments provide a high-resolution chronological framework for dating seismites.

The result is a detailed and continuous record of seismic activity stretching back tens of thousands of years. This record not only provides insights into the frequency and magnitude of past earthquakes but also helps scientists assess seismic hazards in the region today.

Recent studies have pushed the boundaries of what we can learn from seismites. For example, Lu et al. (2020) used statistical analysis of seismite thickness and distribution to estimate the magnitudes of ancient earthquakes in the Dead Sea basin. Their work suggests that it may be possible to reconstruct not just the timing of past earthquakes, but also their intensity, opening new avenues for understanding long-term seismic patterns.

Advances in Core Analysis Techniques

Our ability to read the seismic history recorded in Dead Sea sediments has improved dramatically in recent years, thanks to advances in core analysis techniques. These new methods allow for more detailed and precise examination of sediment cores, revealing information that was previously inaccessible.

One significant advance has been in high-resolution imaging methods. Techniques such as X-ray computed tomography (CT) scanning allow researchers to create detailed 3D images of sediment cores without disturbing the sediments. This enables the identification of subtle structures and variations that might be missed in traditional visual examination (Dulski et al., 2015).

Geochemical analysis techniques have also seen significant improvements. X-ray fluorescence (XRF) core scanning, for instance, allows for rapid, non-destructive elemental analysis of sediment cores at very high resolution – sometimes down to sub-millimeter scales. This can reveal changes in sediment composition that may be related to seismic events or changes in sediment source (Neugebauer et al., 2014).

Perhaps most excitingly, machine learning and artificial intelligence are beginning to play a role in core analysis. These techniques can help identify patterns and anomalies in large datasets that might be missed by human observers. For example, Marwan et al. (2021) used machine learning algorithms to automatically detect and classify seismites in Dead Sea sediment cores, potentially speeding up the process of identifying past seismic events.

These advances have allowed researchers to extract more information from sediment cores than ever before, leading to more detailed and robust reconstructions of past seismic activity.

The Seismic History of the Dead Sea

With these improved techniques, researchers have been able to construct an increasingly detailed picture of the Dead Sea region’s seismic history. The record preserved in the Dead Sea sediments spans hundreds of thousands of years, providing a window into long-term patterns of tectonic activity in the region.

One of the most comprehensive recent studies of the Dead Sea’s seismic history comes from Kagan et al. (2018). They analyzed sediment cores from the Dead Sea Deep Drilling Project, identifying over 220 seismites over the past 220,000 years. This work significantly extended and refined our understanding of the region’s seismic history.

Some key findings from this and other recent studies include:

- Frequency of large earthquakes: The Dead Sea record suggests that large earthquakes (magnitude 6 or greater) occur in the region on average every 1300-1400 years. However, this is not a regular cycle – there are periods of more frequent activity and periods of relative quiescence.

- Clustering of earthquakes: The research reveals that earthquakes in the region tend to cluster in time. There are periods of increased seismic activity lasting several hundred years, separated by quieter intervals.

- Correlation with climate: Interestingly, there appears to be some correlation between seismic activity and climate changes. Periods of increased seismic activity often coincide with times of rapid climate change, though the exact nature of this relationship is still being studied (Lu et al., 2020).

- Regional tectonic implications: The long-term record provides insights into the behavior of the Dead Sea Transform fault system over geological timescales. It suggests that while the overall rate of motion along the fault has remained relatively constant, the way this motion is accommodated (through large earthquakes versus more gradual creep) has varied over time.

- Historical earthquakes: The Dead Sea record includes seismites that likely correspond to historically documented earthquakes, such as the major quake of 31 BCE mentioned by the historian Josephus, which may have damaged Qumran, home of the Dead Sea Scrolls (Kagan et al., 2011).

This seismic history correlates well with other regional records, including historical accounts and archaeological evidence of earthquake damage at sites around the Dead Sea. It also aligns with broader patterns of tectonic activity in the Eastern Mediterranean region.

Next, let’s explore how geologists date these seismic events, allowing us to place them in a broader historical context.

Dating Seismic Events: Improved Techniques and Chronologies

Accurately dating seismic events is crucial for understanding the frequency of earthquakes and correlating them with historical records. In recent years, significant advances have been made in dating techniques, allowing for more precise and reliable chronologies of seismic events in the Dead Sea region.

Radiocarbon dating remains a cornerstone technique for dating organic materials in seismites. This method can be applied to pieces of vegetation, charcoal, or other organic matter trapped within disturbed sediment layers. However, the precision of radiocarbon dating has improved, with accelerator mass spectrometry (AMS) allowing for dating of very small samples (Migowski et al., 2004).

For older sediments beyond the range of radiocarbon dating (about 50,000 years), uranium-thorium (U-Th) dating has proven invaluable. This technique can be applied to carbonate materials such as aragonite, which precipitates from the Dead Sea waters. U-Th dating has allowed researchers to extend the dated portion of the Dead Sea seismic record back hundreds of thousands of years (Torfstein et al., 2015).

A more recent addition to the dating toolkit is optically stimulated luminescence (OSL) dating. This technique measures the time since mineral grains were last exposed to sunlight, making it particularly useful for dating sediments that may lack organic material or carbonates. OSL has been successfully applied to date seismites in the Dead Sea region, providing independent age controls on the seismic chronology (Porat et al., 2019).

More importantly, in recent years it has become possible to integrate multiple dating methods to build robust chronologies. By combining radiocarbon, U-Th, and OSL dates with varve counting (counting of annual sediment layers), researchers have been able to construct highly detailed and reliable timelines of seismic events. This multi-proxy approach allows for cross-validation between different methods and can help resolve discrepancies or ambiguities in individual dating techniques (Kagan et al., 2018).

These improved dating techniques have allowed for more precise correlations between seismites in the Dead Sea sediments and historical earthquakes, as well as a better understanding of long-term patterns in seismic activity.

Archaeological Connections

The seismic history recorded in the Dead Sea sediments doesn’t exist in isolation – it’s intimately connected with the human history of the region. Archaeological sites around the Dead Sea provide tangible evidence of past earthquakes, often corroborating the geological record.

One of the most famous archaeological sites in the region is Qumran, known for the Dead Sea Scrolls. Evidence of earthquake damage at Qumran, including toppled and cracked walls, aligns with seismites in the Dead Sea cores dated to around 31 BCE (Kagan et al., 2011). This earthquake is also mentioned in historical texts by the Roman historian Josephus, providing a rare confluence of geological, archaeological, and historical evidence.

Recent archaeological work has continued to shed light on the impact of earthquakes on ancient societies in the region. For example, excavations at Tel es-Safi/Gath, believed to be the ancient Philistine city of Gath, have revealed evidence of destruction layers that may correspond to major earthquakes recorded in the Dead Sea sediments (Maeir, 2012).

Of particular interest in the context of this series is the ongoing search for the biblical cities of Sodom and Gomorrah. There are two competing sites proposed as the location of the ancient city of Sodom.

The first site, proposed in 1973, is Bab edh-Dhra, located on the edge of the plain south of the Dead Sea. This large, abandoned city once covered nearly 10 acres and contains a city gate that may be where Lot sat, as mentioned in Genesis 19:1. Dr. Bryant Wood and others argue that this southern location fits well with multiple biblical references, including Genesis 10:19 (which places Sodom on Canaan’s southern border), Genesis 14:3,10 (describing armies attacking Sodom from the south), and Ezekiel 16:46 (describing Sodom as south of Jerusalem). Wood’s arguments are summarized in “The Discovery of the Sin Cities of Sodom and Gomorrah” (Bible and Spade, summer 1999).

The second site, proposed more by Dr. Steven Collins, is Tell el-Hammam, located in the Jordan Valley north of the Dead Sea. Collins bases his argument primarily on Genesis 13:10-11, which describes Lot journeying east from between Bethel and Ai, which would place him northeast of the Dead Sea. Collins has been excavating a once-powerful city at this site that was suddenly abandoned. His arguments are presented in his book “Discovering the City of Sodom” (2013). However, this northern location conflicts with other biblical passages that seem to indicate a southern location for Sodom, such as those mentioned above and Genesis 19:23-24, which describes the presence of sulfur in the region, consistent with the area south of the Dead Sea.

This latter site has attracted quite a bit of attention in the past few years. Excavations have revealed evidence of a destruction event around 1650 BCE. The excavators have suggested that this could be the result of a cosmic airburst event, potentially related to the Sodom and Gomorrah narrative (Silvia et al., 2021). However, the evidence is intriguing but this interpretation remains controversial within the archaeological community.

Regardless of which is correct it is apparent that most biblical scholars agree that one of the remains of ancient settlements near the Dead Sea represent the former site of Sodom and each of these sites are found 800 to 1300 feet below sea level again confirming that the Dead Sea shore has been restricted to 1300 feet or lower for all of recorded history. This places strict boundaries on any young-earth models of the origins of the Dead Sea and Jordan Valley.

Analysis of Steve Austin’s Work on Biblical Earthquakes

In discussing the seismic history of the Dead Sea and its potential connections to biblical narratives, it’s important to address the work of Dr. Steve Austin, a geologist associated with young-earth creationism. Austin has published several papers arguing that Dead Sea seismites can be correlated with specific biblical events, including the destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah, and earthquakes mentioned in the Book of Amos and others, thereby confirming the faithful witness of the scriptures.

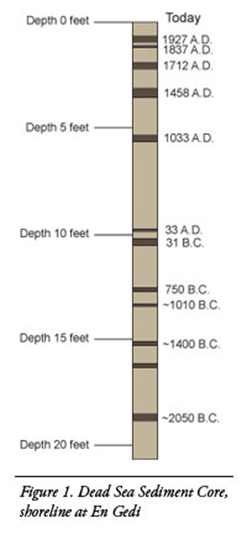

It brings me some relief that I can discuss this young-earth creationist’s work and say that I can agree with its major findings. This article accurately reports and describes how a sediment record of historical earthquakes has been preserved in the sediments deposited in the Dead Sea. In his 2010 Institute for Creation Research article, “Greatest Earthquakes of the Bible,” Austin describes a 2001 study of a 40-foot sediment core pulled from close to the present-day shore of the Dead Sea:

Recently, geologists have investigated the 4,000-year chronology of earthquake disturbances within the uppermost 19 feet of laminated sediment of the Dead Sea. Hypersaline waters preserve seasonally laminated sediment because organisms cannot live or burrow in the bed of the lake. As a result, only a nearby earthquake (or very large distant earthquake) can homogenize the lake’s uppermost sediment layers, producing a “mixed layer” devoid of laminations. A sketch of a sediment core from the west side of the Dead Sea appears in Figure 1. The sketch shows the depth of the “mixed layers” within the laminated sediment sequence. Two deeper mixed layers in the Dead Sea are datable from historical, archaeological, and geological associations with faulting—the earthquakes of 31 B.C. (the Qumran earthquake) and 750 B.C. (Amos’ earthquake). Other earthquakes are represented in the Dead Sea sediment core with dates approximated by assuming a steady rate of sedimentation.

…. Two Early Bronze Age archaeological sites southeast of the Dead Sea (Bab edh-Dhra and Numeira) reveal evidence of catastrophic collapse and burning along the eastern border fault of the Dead Sea Transform Fault. These two sites are likely the remains of Sodom and Gomorrah. A thick disturbed zone within the Dead Sea sediment core, assignable to the Sodom and Gomorrah event, occurs at a depth of about 18.5 feet.

To Austin’s description, I would add that the 19-foot sediment profile was obtained from the wall of a canyon that was carved in the past decade due to the Dead Sea’s rapid evaporative lowering. The “mixed layers” Austin refers to have a technical name: seismites. The thickness of the seismite can be used to infer the magnitude of the earthquake. There are similar earthquake signatures found in ocean-floor sediments. The 2050 BC seismite (see figure) might be associated with the destruction of Sodom mentioned in Genesis 19. If that is the case, then this sediment core tells us that the Dead Sea must have covered the area where these sediments were observed at the time of the earthquake, since the seismites would not have formed if the lake had been at a level it is today or lower. But still lower than any archeological site in the area including Jericho.

In addition, the original research papers were able to identify almost every major written record of earthquakes in these layers of sediment. Thus, the Dead Sea had to have been above its current levels during the time of these earthquakes. This is additional evidence that the Dead Sea is lower today than any time in recorded history.

In Part XI we will take a close look at another creationist’s, Brian Thomas, take on the sediment cores taken from the Dead Sea. For now we can note that Thomas claims that the pebble layer, which is nearly 1000 feet lower than this seismite that Austin identifies, represents the time of Sodom’s destruction. If Austin and the consensus view of geologists are correct that the 2050 BC earthquake is recorded in this sediment profile, then Thomas’ claim must be incorrect.

Confirmation of biblical events — Yes! Confirmation of a young earth — No!

I agree! The 4000-year-old series of sediments provides a wonderful confirmation of major earthquake events in the Bible, just as Austin claims. So is this all good news for young-earth creationists? Not so fast.

We must ask ourselves: What is below this 4000-year-old seismite just 18.5 feet below the surface? Unfortunately for young earth creationists, thousands of feet of additional layers of sediments and salt deposits lie below. The deeper we go, the more questions arise for the creationist.

It’s not that modern geology undermines the eye-witness records of earthquakes recorded in scriptures at all. Rather, it offers an overwhelming challenge to the YEC’s global-flood hypothesis.

Fortunately, for Christians, flood geology is not an inspired fact of the Bible, but rather an inference derived by certain, and likely flawed, interpretations of some passages of the Bible. The Dead Sea data, including the earthquake data presented in this chapter, should be cause for young-earth creationists to reassess their hermeneutic methods and assumptions about earth’s history. If you have followed the other parts of this series, you should be able to identify several observations of the Dead Sea that greatly trouble YEC flood geology, but let me just point out the most obvious one.

The 4000-year old chronology recording all events from Genesis 12 to the present day is contained in just nineteen feet of sediments!

If sediments nineteen feet below the surface do represent 4000-year-old events, and all the evidence points to this being true, what does the young earth advocate do with the remaining 15,000+ feet of sediments found below them? The obvious response is to relegate them to a global flood, but not for any reason other than it is the only choice that can allow them to maintain their young earth worldview.

Interestingly and importantly, Austin neglects in his article to mention that the scientists who published the work that he has referenced had previously examined a sedimentary column that represented the past 50,000 years (Kagan et al., 2011). Those scientists were looking for earthquakes over that longer time frame and found many that were much deeper in the sediment column than the one that Austin recognized as representing the events of 4000 years ago. What should Austin, or any young earth creationist for that matter, do with evidence that earthquakes occurred another 20 feet below the earthquake that Austin is claiming occurred in 2050 BC?

Remember: the evidence that the Dead Sea dried out in the past was found at least another 700 feet below this small nineteen-foot sediment core. These sedimentary layers include thousands of layers of precipitated salts, which are surely the result of past precipitates from a salt-laden lake that had resided in this valley for hundreds of thousands of years. There is nothing about the sediments below Austin’s nineteen feet of sediment that would suggest that they were laid down under conditions significantly different from those that are experienced in the Dead Sea region over the past 4000 years.

Where is the evidence for a global flood here? YEC flood geologists would point to the rocks that make up the walls of the Jordan Valley that resulted from plate tectonic forces separating the land. That land, the Judean mountains and the Judean plateau to the west are made up of thousands of feet of sedimentary rocks which flood geologists believe must have all formed during the year of the Flood. If the rifting of this land to create the Jordan Valley occurred at the end of the Flood year, how did the Jordan Valley become filled with 10 to 15 thousand feet of sediments and precipitated salts?

Creationists use carbon (C14) dating and uniformitarian assumptions when it is convenient to them

I found the following sentence in Austin’s article very enlightening: “Other earthquakes are represented in the Dead Sea sediment core with dates approximated by assuming a steady rate of sedimentation.”

A “steady rate of sedimentation” is an interesting phrase, since it is a uniformitarian assumption, the kind of assumption that YECs regularly attack. Here we see that Austin has accepted the use of a geological principle that is so often maligned in the creationist literature. Of course, he doesn’t call attention to the fact that here he is accepting the principle of uniformitarianism, and yet there it is.

The same is true for C14 dating, which is another thing that YECs often attack. Austin doesn’t tell his readers that the dates for some of the seismites were determined by C14 dating of organic materials found in the seismite layers. With dates attached to some of the seismites, the rest of the seismite ages could be estimated using a steady state (i.e., uniformitarianism) assumption about sedimentation rates. Austin seems to accept this with no problem.

This is equivalent to using index fossils to date layers of rock. Again, it’s a principle that is routinely attacked by creationists.

What we have here is a case where Austin is accepting the techniques and assumptions of the secular research community because the results they provide suit his purposes. The C14 data and the steady state assumption lead to predicted earthquake dates that fit the Biblical record of earthquakes very well. So it is understandable that Austin would be attracted to this particular data set. To question those assumptions would be to remove a good source of extrabiblical evidence for the events recorded in the Bible.

But what about earthquakes in the sediment record that are below the 2050 BC earthquake? Is Austin, or any other young-earth creationist, going to accept the C14 dates and steady state assumption of deposition that estimates those earthquakes to have occurred at 5000 BC or 10,000 BC?

No, in true fideistic fashion, they won’t accept those dates, for no other reason than they can’t be true. C14 dating and relatively uniform deposition rates are accepted for the past 4000 years but even in the face of similar evidence of a much longer timeline that evidence is discounted and said to be the result of processes that acted very differently than we observe today.

The sediment record does support the biblical record!

I believe it is very likely that the disturbed layers in the top 19 feet of the sediment deposited near the bottom of the Dead Sea basin do represent the very earthquakes that both Austin and the original researchers have assigned to them. These dates corroborate the biblical record of those earthquakes (i.e., Sodom and Gomorrah). But I wonder if Austin has ever contemplated the consequences of accepting this interpretation of the data? At the same time that it supports the biblical timeline, it contradicts the young-earth view that the Dead Sea is less than 4350 years old.

And let’s not forget about that dried-up Dead Sea evidence we discussed in Part V of our series. The pebble layer indicating a nearly dry Dead Sea lies about 700 feet below Austin’s 19-foot core. In the YEC model, when exactly did the Dead Sea have time to dry up, refill, and deposit 700 feet of sediment, all within a few hundred years after the Flood?

This is the conundrum that creation scientists get themselves into when they examine the geology of the Promised Land. They want and need to accept conventional geological interpretations and methods because those methods yield results that match the last 4000 years of recorded history, as found in the Bible. But the same methods applied to the whole record of this region yield no evidence of a global flood, but rather a long history of development of the geological features of the Promised Land.

Flood geology does not offer an explanatory program, but rather creates a horror show of contradictory conclusions when it is applied to real data. Both Brian Thomas and Steve Austin want to accept some findings of modern geology because they can see that the data lend support to the Bible. But in accepting this research, they create hundreds of scientific and observational problems for their young-earth hypothesis. Often, this is why many creationists find it more convenient to simply dismiss new findings and try to explain them away rather than embrace them.

Austin’s article is right to show that the biblical record is supported by geological evidence. But he misleads his audience when he chooses to ignore data that undermine his young-earth hypothesis of Earth’s history.

Addendum: What about the fire and brimstone that rained down on Sodom and Gomorrah as recorded in Genesis?

In my earlier description of the Dead Sea basin, I didn’t mention another very important feature of the Dead Sea plain, especially around the southern end of the lake. There are many bitumen deposits there and regions of high sulfur (brimstone). Bitumen is like asphalt and is a form of oil. It was highly prized in the Ancient Near East, and the Egyptians were known to collect and mine it in the region. Today, asphalt seeps into the lake and floats to the surface of the Dead Sea. There were pits dug around the Dead Sea in ancient times, and a thriving industry of bitumen collection existed, probably supporting the many ancient cities found in the region such as Zoar south of the Dead Sea.

The bitumen is concentrated along fault lines because this is where the earth is cracked vertically, allowing the oil to move up toward the surface. So if there is a large earthquake, the energy of the movement will occur within these deposits. It is plausible, then, that a large earthquake could have disturbed a large vein, igniting the oily residues and creating a thick black smoke that would have filled the valley. In Genesis, there is reference to “pits” that those fleeing the cities in battle fell into. It seems likely to me that these are the pits that result from sinkholes caused by salt caves and any large earthquakes at the time may have opened up new ones, but it could be this is a reference to the many pits dug for bitumen production.

At the same time, the earthquake itself may have been caused by volcanic activity. Because the earth’s plates are moving apart, the crack that has formed has a very thin crust compared to the plates, and so lava from the Earth’s mantle can more easily puncture up through that crust and appear on the surface. Near the Sea of Galilee, there are thick layers of volcanic rock from ancient eruptions that poured lava into the Dead Sea valley. South of the Dead Sea, there are some small volcanic vents. Most of these are thought to have been active much earlier than 4000 BC, but some activity is possible, and the presence of lava near the surface, even if it doesn’t appear above the surface, would introduce sulfur compounds into the groundwater and bitumen deposits. When the bitumen caught fire and exploded, there would have been a distinct sulfur smell even without a volcanic eruption at the same time.

The Conundrum for Creation Scientists

This situation highlights a common dilemma faced by creation scientists when dealing with geological evidence from the Holy Land. They often want to accept conventional geological interpretations when they corroborate biblical history. However, they then face the challenge of explaining why these same methods shouldn’t be applied to older sediments.

The result is a sort of geological double standard. Methods and assumptions are accepted when they produce results that fit the YEC timeline, but rejected when they indicate a much older Earth. This inconsistency creates significant problems for the internal logic of flood geology explanations.

Additional Challenges to YEC Framework

Beyond the issues already discussed, there are several other aspects of the Dead Sea sediment record that pose challenges to the YEC framework:

- Long-term earthquake frequency patterns: Studies of the Dead Sea sediments reveal patterns of earthquake clustering over millennia, with average recurrence intervals for large quakes of about 1300-1400 years (Kagan et al., 2018; Ken-Tor, 2001). These long-term patterns are difficult to squeeze into a few-thousand-year timescale.

- Correlation between seismic activity and climate changes: Researchers have found intriguing links between periods of increased seismic activity and rapid climate shifts (Lu et al., 2020). These correlations span tens of thousands of years, far exceeding the YEC timeline.

- Multiple dating method agreement: The chronology of the Dead Sea sediments isn’t based on just one method. Radiocarbon dating, uranium-thorium dating, optically stimulated luminescence, and varve counting all provide consistent ages (Torfstein et al., 2015). This multi-method agreement is powerful evidence for the reliability of these dating techniques.

- Varved sediments: The Dead Sea contains annually laminated (varved) sediments, providing a year-by-year record stretching back tens of thousands of years (Prasad et al., 2009). Explaining the formation of tens of thousands of annual layers in a post-Flood YEC timeframe is problematic.

- Regional tectonic implications: The long-term record preserved in the Dead Sea sediments provides insights into the behavior of the Dead Sea Transform fault system over geological timescales (Marco et al., 1996). This long-term tectonic history is difficult to compress into a few thousand years.

- Archaeological connections: The seismite record correlates well with archaeological evidence of earthquake damage at sites around the Dead Sea, such as at Qumran (Kagan et al., 2011). Fitting the rise and fall of multiple civilizations, along with their destruction by earthquakes, into the short YEC chronology is challenging.

These additional lines of evidence, when combined with the issues we’ve already discussed, present a formidable challenge to young-earth interpretations of Dead Sea geology. They underscore the importance of considering the full range of evidence when interpreting Earth’s history.

The Bigger Picture: Geological Evidence vs. YEC Interpretation

As we step back and look at the bigger picture, it becomes clear that the Dead Sea sediments present a consistent narrative of Earth’s history that extends far beyond the confines of the young-earth timeline. This consistency is one of the most powerful arguments against the YEC interpretation.

Consider this: the same geological methods that accurately correlate seismites with historical earthquakes over the past 4,000 years continue to work as we go deeper into the sedimentary record. The annual layers (varves) don’t suddenly change character. The radiocarbon dates don’t abruptly become unreliable. The patterns of earthquake recurrence don’t inexplicably shift. Instead, we see a continuous record that stretches back hundreds of thousands of years.

This consistency poses a significant challenge to YEC models. If these methods are reliable for recent history – reliable enough that creationists like Austin use them to corroborate biblical accounts – what justification is there for arbitrarily deciding they become unreliable beyond a certain point?

Moreover, the Dead Sea is not an isolated case. Similar long-term records are found in ice cores, ocean sediments, and other lakes around the world. All of these records tell a consistent story of gradual change over vast periods of time, punctuated by periodic rapid events like earthquakes or climate shifts.

For the YEC model to be viable, it needs to explain not just isolated pieces of evidence, but the entire geological record. It needs to account for why multiple independent dating methods agree with each other, why we see clear patterns of climate change and tectonic activity over long periods, and why the geological processes we observe today seem to match those recorded in ancient sediments.

Conclusion

As we wrap up this exploration of the Dead Sea’s seismic history, we find ourselves with a wealth of evidence that both supports biblical historicity and challenges young-earth chronology. It’s a perfect example of how science and faith can intersect in complex and sometimes surprising ways.

The seismite record in the Dead Sea sediments provides remarkable confirmation of earthquake events recorded in the Bible. It’s a testament to the accuracy of ancient historical accounts and the power of geological methods to illuminate the past. In this sense, the work of researchers like Steve Austin contributes valuable insights to our understanding of biblical history.

However, the very same evidence that corroborates biblical earthquakes also points to an Earth history far older than the YEC timeline allows. The thousands of feet of layered sediments, the long-term patterns of earthquake recurrence, the correlation with climate changes, and the consistency of multiple dating methods all suggest a history spanning hundreds of thousands of years.

For those committed to a young-earth view, these findings present a significant challenge. They call for a reevaluation of how geological evidence is interpreted within the YEC framework. It’s not enough to selectively accept scientific methods when they seem to support a preferred timeline while rejecting them when they don’t. A robust scientific theory needs to account for all the evidence, not just cherry-picked portions.

As Christians engaged in scientific inquiry, we’re called to pursue truth wherever it leads. Sometimes that pursuit might challenge our preconceptions or require us to rethink our interpretations of scripture. But I believe that ultimately, a fuller understanding of God’s creation can only enhance our appreciation of its Creator.

The Dead Sea, with its rich geological and historical record, invites us to dig deeper – both literally and figuratively. It challenges us to grapple with the complexities of Earth’s history and to continually refine our understanding based on the evidence before us.

As we close this portion of our Dead Sea exploration, I hope you’ve gained a new appreciation for the intricate ways in which geology, history, and faith intersect. The story written in these sediments is a testament to the power of scientific inquiry to illuminate the past and to the enduring relevance of ancient texts. It’s a story that continues to unfold, inviting further research and deeper understanding.

References:

Agnon, A., Migowski, C., & Marco, S. (2006). Intraclast breccias in laminated sequences reviewed: Recorders of paleo-earthquakes. Geological Society of America Special Papers, 401, 195-214.

Austin, S.A. (2010). Greatest Earthquakes of the Bible. Acts & Facts, 39(10), 12-15.

Collins, Steven. (2013). Discovering the City of Sodom: The Fascinating, True Account of the Discovery of the Old Testament’s Most Infamous City. Howard Books.

Dulski, P., Brauer, A., & Mangili, C. (2015). Combined µ-XRF and microfacies techniques for lake sediment analyses. In Micro-XRF Studies of Sediment Cores (pp. 325-349). Springer, Dordrecht.

Kagan, E. J., Agnon, A., Bar-Matthews, M., & Ayalon, A. (2011). Dating large infrequent earthquakes by damaged cave deposits. Geology, 33(4), 261-264.

Kagan, E. J., Langgut, D., Boaretto, E., Neumann, F. H., & Stein, M. (2015). Dead Sea levels during the Bronze and Iron ages. Radiocarbon, 57(2), 237-252.

Kagan, E. J., Stein, M., & Marco, S. (2018). Integrated paleoseismic chronology of the last glacial Lake Lisan: From lake margin seismites to deep-lake mass transport deposits. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth, 123(4), 2806-2824.

Kagan, E. J., Stein, M., Agnon, A., & Neumann, F. (2011). Intrabasin paleoearthquake and quiescence correlation of the late Holocene Dead Sea. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth, 116(B4).

Ken-Tor, R., Agnon, A., Enzel, Y., Stein, M., Marco, S., & Negendank, J.F.W. (2001). High-resolution geological record of historic earthquakes in the Dead Sea basin. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth, 106(B2), 2221-2234.

Lu, Y., Wetzler, N., Waldmann, N., Agnon, A., Biasi, G. P., & Marco, S. (2020). A 220,000-year-long continuous large earthquake record on a slow-slipping plate boundary. Science advances, 6(48), eaba4170.

Maeir, A. M. (2012). The Tell es-Safi/Gath Archaeological Project 1996–2010: Introduction, Overview and Synopsis of Results. In Tell es-Safi/Gath I: The 1996–2005 Seasons (pp. 1-88). Harrassowitz Verlag.

Marco, S., Stein, M., Agnon, A., & Ron, H. (1996). Long‐term earthquake clustering: A 50,000‐year paleoseismic record in the Dead Sea Graben. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth, 101(B3), 6179-6191.

Marwan, N., Trauth, M. H., Vuille, M., & Kurths, J. (2021). Nonlinear time series analysis of climate variability. In Paleoclimatology (pp. 129-154). Springer, Cham.

Migowski, C., Agnon, A., Bookman, R., Negendank, J. F., & Stein, M. (2004). Recurrence pattern of Holocene earthquakes along the Dead Sea transform revealed by varve-counting and radiocarbon dating of lacustrine sediments. Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 222(1), 301-314.

Neugebauer, I., Brauer, A., Schwab, M. J., Waldmann, N. D., Enzel, Y., Kitagawa, H., … & Frank, U. (2014). Lithology of the long sediment record recovered by the ICDP Dead Sea Deep Drilling Project (DSDDP). Quaternary Science Reviews, 102, 149-165.

Porat, N., Faerstein, G., Medialdea, A., & Murray, A. S. (2015). Re-examination of common extraction and purification methods of quartz and feldspar for luminescence dating. Ancient TL, 33(1), 22-30.

Prasad, S., Vos, H., Negendank, J. F., Waldmann, N., Goldstein, S. L., & Stein, M. (2009). Evidence from Lake Lisan of solar influence on decadal-to centennial-scale climate variability during marine oxygen isotope stage 2. Geology, 37(1), 71-74.

Silvia, P. J., Bunch, T. E., LeCompte, M. A., Daly, T. K., Schultz, P. H., Schweitzer, J. C., … & Wegner, W. W. (2021). A Tunguska sized airburst destroyed Tall el-Hammam a Middle Bronze Age city in the Jordan Valley near the Dead Sea. Scientific Reports, 11(1), 1-64.

Torfstein, A., Goldstein, S. L., Kushnir, Y., Enzel, Y., Haug, G., & Stein, M. (2015). Dead Sea drawdown and monsoonal impacts in the Levant during the last interglacial. Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 412, 235-244.

Wood, Bryant G. (1999). “The Discovery of the Sin Cities of Sodom and Gomorrah.” Bible and Spade. Summer 1999.