As we continue our journey through the geological wonders of the Dead Sea region, we find ourselves facing many questions that have implications for how we understand Earth’s history and interpret Scripture. In previous chapters, we’ve explored the formation of the Dead Sea, the ancient Lake Lisan, and the seismic history recorded in the sediments. Now, we turn our attention to the archaeological evidence of human habitation in the Jordan Valley – evidence that presents not only a challenge to young-earth creationist interpretations of Earth’s history but is an observation that all Christians must address.

As a Christian who takes both faith and science seriously, I approach the topic, the chronology of human in history, with a mix of fascination and trepidation. I’m aware that discussions about the age of the Earth and our place in it in particular, can be divisive within the church, often pitting brother against brother in conflict. Yet, I believe that as followers of Christ, we are called to pursue truth wherever it leads us, trusting that all truth is God’s truth. It’s in this spirit that I invite you to join me in examining the evidence with open minds and humble hearts.

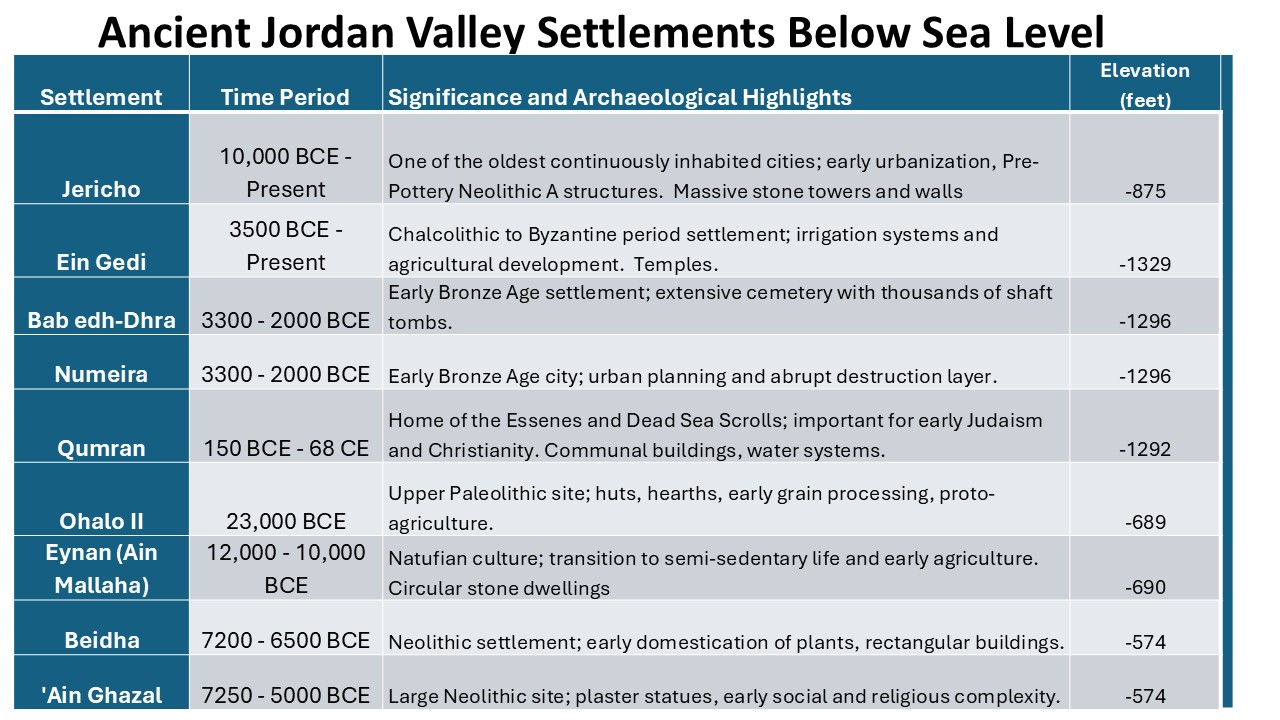

Here we will focus on the archaeological remains of ancient cities in the Jordan Valley and how their history aligns – or doesn’t align – with the young-earth creationist timeline. This timeline typically suggests that the Jordan Valley originated just 4,350 years ago and, by 4,100 to 4000 years ago, looked much as it does today. This leaves a mere 250 to 3050-year window for all the geological and archaeological evidence we’ve encountered in our series to fit into. As we’ll see, this compressed timeline creates significant challenges when confronted with the wealth of evidence from the ground, and in this case, the human artifacts, beneath our feet.

The Geological Context of the Jordan Valley

Before we examine the archaeological evidence, it’s crucial to remind ourselves of the geological stage upon which human history has played out in this region. As we have seen in previous part of this series, the Jordan Valley is not merely a depression in the Earth’s surface; it’s a dynamic landscape shaped by powerful forces over immense periods of time.

At the heart of the valley’s formation is the Dead Sea Transform fault system, a major tectonic boundary where the Arabian Plate and the African Plate slide past each other (Garfunkel & Ben-Avraham, 1996). This lateral movement has been occurring for millions of years, gradually tearing the landscape apart and creating the deep basin that characterizes the valley today.

But tectonic forces aren’t the only players in this geological drama. Erosion and sedimentation have also played crucial roles. Over millennia, water and wind have eroded the surrounding highlands, depositing sediments into the valley floor. These processes have contributed to the fertile soils that supported ancient agriculture and continue to do so today.

None of these steps in the geological evolution of the current topography of the Levant region are rapid events but occur over extensive periods. The shaping of the Jordan Valley cannot be confined to a 250-year timeframe between the Flood and earliest written accounts of this region as proposed by young-earth creationism. Instead, the evidence points to a landscape molded over at least hundreds of thousands of years, a testament to the Earth’s dynamic nature.

If we find evidence of cities, hunting implements, hearths for cooking or other artifacts of obvious human invention lying on the surface of the landscape of the Dead Sea basin, basic geological principles tells us that these artifacts must have been left here in these locations following development of the landscape itself.

Ancient Settlements Below Sea Level

Now, let’s turn our attention to the remarkable human history preserved in the Jordan Valley. This region is home to some of the world’s oldest continuously inhabited cities, many of which lie well below sea level. Their very existence and the layers of human occupation they contain present a formidable challenge to the young-earth timeline.

Jericho: An Ancient City

Often cited as one of the world’s oldest continuously inhabited cities, Jericho offers a window into human history dating back to around 10,000 BCE (Kenyon & Holland, 1981). Located in the lower Jordan Valley near the Dead Sea, this ancient city sits well below sea level at -875 feet!

Excavations at Tell es-Sultan, the archaeological site of ancient Jericho, have uncovered layers upon layers of consecutive human occupation. One of the most remarkable discoveries is the massive stone tower and wall from what archaeologist call the Pre-Pottery Neolithic A period (PPNA), suggesting a high level of social organization and engineering skill (Bar-Yosef, 1986). These structures indicate that Jericho was more than just a settlement; it was a significant center with complex societal structures.

The archaeological evidence from Jericho challenges any notion that the city’s history could be compressed into just a few millennia. The depth of the archaeological layers, the sophistication of the structures, and the gradual changes in material culture all point to protracted history of human occupation at this location. It also places strict upper limits (-875 feet) on the upper most shoreline height of the Dead Sea during the lifetime of this city. This is critical for our goal of understanding the timetable and origins of the Dead Sea in relation to the scriptures.

IMAGE of Cross Section of Jericho tell

Ein Gedi: An Oasis in the Desert

Moving south along the western shore of the Dead Sea, we encounter Ein Gedi, an oasis that has attracted human settlement since around 3500 BCE during the Chalcolithic period (Hirschfeld, 2006). It lies 1,329 feet (405 meters) below sea level, making it the lowest-elevation city in the world and only a bit more than 100 feet above the modern shoreline of the Dead Sea. This restricts the fluctuations of the Dead Sea shore during human recorded history even more than Jericho. Its freshwater springs and fertile land made it an ideal location for agriculture and habitation in an otherwise inhospitable environment.

Archaeological excavations have revealed a wealth of artifacts, including temples, agricultural installations, and sophisticated irrigation systems. Ein Gedi flourished during the Iron Age and later became a significant site during the Byzantine period. The continuity of settlement here underscores the long-term human presence in the region.

Bab edh-Dhra and Numeira: Echoes of Sodom and Gomorrah?

Further south along the Dead Sea’s eastern shore lie the ancient sites of Bab edh-Dhra and Numeira. These Early Bronze Age cities, dating from approximately 3300 to 2000 BCE, are sometimes associated with the biblical cities of Sodom and Gomorrah (Rast & Schaub, 2003).

Bab edh-Dhra features an extensive cemetery with thousands of shaft tombs, indicating a complex society with specific burial practices. Numeira, while smaller, provides valuable insights into urban planning and architecture of the period. The destruction layers at these sites suggest they were abruptly abandoned, adding to their historical intrigue.

Qumran: Home of the Dead Sea Scrolls

Perhaps best known for the discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls, Qumran was occupied from around 150 BCE to 68 CE (Magness, 2021). This settlement offers a unique glimpse into the lives of the Essenes, a Jewish sect that lived in relative isolation.

The site’s location below sea level and its proximity to the Dead Sea provided the isolation the community sought. The preservation of the scrolls in this arid environment has been invaluable to our understanding of early Judaism and the origins of Christianity.

While Qumran’s occupation falls within the timeframe accepted by young-earth creationists, its existence relies on the stable environmental conditions of the Dead Sea region – conditions that, as we’ve seen in previous posts, took far longer to develop than the young-earth model allows.

As we consider these ancient settlements, all located well below sea level, we’re confronted with a compelling body of evidence that challenges the young-earth timeline. The depth of occupation layers, the sophistication of the structures, and the clear progression of cultural development all point to a much longer history of human habitation in the Jordan Valley than 4,350 years.

For those of us who take the Bible seriously, this evidence invites us to reconsider how we interpret the early chapters of Genesis. Could it be that God’s methods of creation are more complex and time-consuming than we initially thought? Might our understanding of biblical chronology benefit from the insights provided by archaeology and geology?

Prehistoric Human Presence in the Jordan Valley

As if cities on the Dead Sea plain that are 4000 to 10,000 years old were enough, as we venture further back in time, the evidence for human occupation in the Jordan Valley becomes even more challenging to reconcile with a young-earth timeline. The archaeological record reveals complex story of modern human activity stretching back tens of thousands of years.

Paleolithic Occupation

There are numerous sites with stone tools that hint at very ancient occupation, but we will restriction ourselves to sites in the Dead Sea valley that are well dated and studies. One of these sites is named Ohalo II, dating to around 23,000 years ago (Nadel & Werker, 1999). Located near the southwestern shoreline of the Sea of Galilee (Lake Kinneret), Ohalo II offers a rare snapshot of Upper Paleolithic life. The site’s exceptional preservation, due to rapid burial by sediment and water, has revealed huts, hearths, and an array of plant remains. Evidence of grinding stones suggests that these early inhabitants processed grains, hinting at proto-agricultural practices much earlier than previously thought.

The Natufian Culture and the Birth of Agriculture

Transitioning to what paleontologist call the Epipaleolithic period, approximately 20,000 to 10,000 BCE, we encounter the Natufian culture—a cultural bridge between nomadic hunter-gatherers and settled agricultural societies. At Eynan (Ain Mallaha) located in the Hula Valley north of the Sea of Galilee, dating from about 12,000 to 10,000 BCE, archaeologists have uncovered circular stone dwellings and communal graves (Valla, 1995). This site illustrates some of the earliest known instances of semi-sedentary living.

At these sites we can see an apparent shift towards cultivating wild cereals. They harvested wild grains and may have begun experimenting with plant cultivation, setting the stage for the agricultural revolution. The Jordan Valley’s fertile environment provided an ideal backdrop for these early developments in agriculture.

Neolithic Innovations

The Neolithic period shows significant advancements in technology, architecture, and social organization. Jericho, during the Pre-Pottery Neolithic A period (10,000 – 9,000 BCE), is a prime example (Kenyon & Holland, 1981). Excavations have revealed massive stone walls and a tower, suggesting not only architectural ingenuity but also a need for defense or flood control.

Further east, sites like Beidha and ‘Ain Ghazal offer additional insights. Beidha, dating from around 7,200 to 6,500 BCE, showcases rectangular buildings and evidence of early plant domestication (Byrd, 2005). ‘Ain Ghazal, occupied from about 7,250 to 5,000 BCE, is remarkable for its size and the discovery of life-sized plaster statues (Rollefson & Kafafi, 2007). These statues are among the earliest large-scale human representations, indicating complex religious or ritualistic practices.

The technological and cultural innovations of these Neolithic communities didn’t happen overnight. They reflect gradual developments in farming techniques, animal domestication, and social organization. Genetic studies of plant and animal remains from these sites show the slow process of domestication over thousands of years (Lev-Yadun, Gopher, & Abbo, 2000). This period marks a significant turning point in human history, with the Jordan Valley at its heart.

Additional Processes that Corroborate Long Timespans

To further illustrate the deep history of the Jordan Valley and corroborate the observations made from archaeological sites, let’s examine two fascinating geological features that serve as natural time capsules: travertine deposits and speleothems.

Travertine Deposits: Nature’s Slow-Motion Builders

Travertine deposits are a type of limestone formed through the precipitation of calcium carbonate (CaCO₃) from mineral-rich waters, typically in areas with hot springs, caves, or waterfalls. They are often found at archaeological sites in the Jordan Valley because those sites are established around natural spring with high calcium carbonate levels. They are nature’s own time-lapse cameras, recording environmental changes over thousands of years. These calcium carbonate deposits have been observed to form incredibly slowly, typically less than 1 mm per year.

At Jericho, travertine deposits up to 1.5 meters thick have been found associated with Neolithic structures. Since they formed on structures such as water ducts they formation must be accounted for since the occupation of that site. Even at a generous estimate of 1 mm per year, that’s 1500 years of continuous formation. Some of these deposits are found on structures dating back to 8000 BCE—10,000 years ago, more than twice the age allowed by the young-earth timeline for the entire universe!

Dr. Amos Frumkin’s research shows that the travertine deposits at Jericho not only support the conclusions of other archaeological dating methods but also provide valuable data on past climate conditions in the region (Frumkin et al., 2011).

Speleothems: Underground Climate Archives

In the caves of Soreq and Peqi’in in Israel, not far from the Jordan Valley, researchers have found speleothems that provide a continuous climate record spanning the last 185,000 years (Bar-Matthews et al., 2003). That’s over 42 times longer than the entire young-earth timeline!

These underground time capsules form as water drips through limestone, depositing tiny amounts of minerals with each drop. By analyzing these layers, scientists can reconstruct past rainfall patterns and temperatures with remarkable precision.

Dr. Miryam Bar-Matthews and her colleagues have used these speleothems to track climate changes that align with known historical events. For example, they’ve identified periods of severe drought around 8,200 years ago and again about 4,200 years ago—events that coincide with major cultural transitions in the archaeological record mentioned earlier.

These slow-forming geological features serve as natural chronometers, ticking away the millennia in a steady, measurable rhythm. They provide independent confirmation of the ancient timelines suggested by archaeological evidence, and they paint a picture of gradual, long-term changes in climate and environment that simply cannot be squeezed into a few thousand years.

Contradictions with Young-Earth Creationism

Given this extensive archaeological record, the young-earth creationist claim that the Jordan Valley is only about 4,350 years old presents a significant challenge. This perspective suggests that the valley—and indeed, the Earth—was formed in a much shorter timespan, often tied to a literal interpretation of Genesis.

Mapping these ancient sites reveals a fascinating pattern of human habitation along the Jordan Valley and its environs. From Eynan in the north to Jericho in the south, the distribution of these settlements underscores the valley’s possible role as a corridor for migration and cultural exchange.

The environmental diversity—from lush valleys to arid deserts—required early humans to adapt in innovative ways. They developed strategies for hunting, gathering, farming, and building that were suited to their specific surroundings. This adaptability is a testament to human resilience and ingenuity.

Notably, all of these technologies appear to predate the type of culture and technology that we would associate with Abraham and the people who lived in the land at this time. Given these stone tool and other artifacts are found scattered throughout the Jordan Valley either on the surface or buried under only a few layers of sediment strongly suggests that even prior to the time of Abraham some 4000 years ago the Jordan Valley had the same topology or geographical shape and characteristics that it has today.

The evidence from the small sample of possible archeological sites we could have explored, directly contradicts the young-earth timeline. The sheer depth of stratified cultural layers at these sites cannot be compressed into a few thousand years without disregarding fundamental principles of archaeology and geology.

To accept the young-earth timeline, one would have to dismiss a vast body of empirical data collected through rigorous scientific methods. The discrepancies aren’t minor—they involve orders of magnitude that fundamentally alter our understanding of human history.

As a Christian grappling with this evidence, I’m struck by the depth of human history it reveals. These findings challenge us to expand our understanding of God’s creation and the timescales over which He works. They invite us to marvel at the long journey of human development and to appreciate the intricate ways in which God has guided His people through time. Much more on this in Part X of this series.

How Do We Know that these Dates are Correct?

I understand that if you’re coming from a young-earth perspective, the dates I’ve presented for these ancient settlements might seem impossibly old. After all, they extend well beyond the roughly 4,500-year timeline that young-earth creationists typically work with. It’s natural to be skeptical when confronted with information that challenges our existing beliefs. But I invite you to consider the evidence with an open mind.

Remember, as Christians, we believe that God is the author of both Scripture and nature. If we’re interpreting either one correctly, there shouldn’t be a conflict. So let’s take a closer look at how scientists determine these ancient dates. The dates I’ve shared aren’t just arbitrary numbers plucked from thin air. Are they the result of some observer or scientist error? If not, then it is evidence that we need to grapple with.

I am convinced they’re the result of careful, methodical research using multiple lines of evidence often performed by Christians. You might be surprised at how robust and consistent the evidence really is.

Overview of multiple dating methods

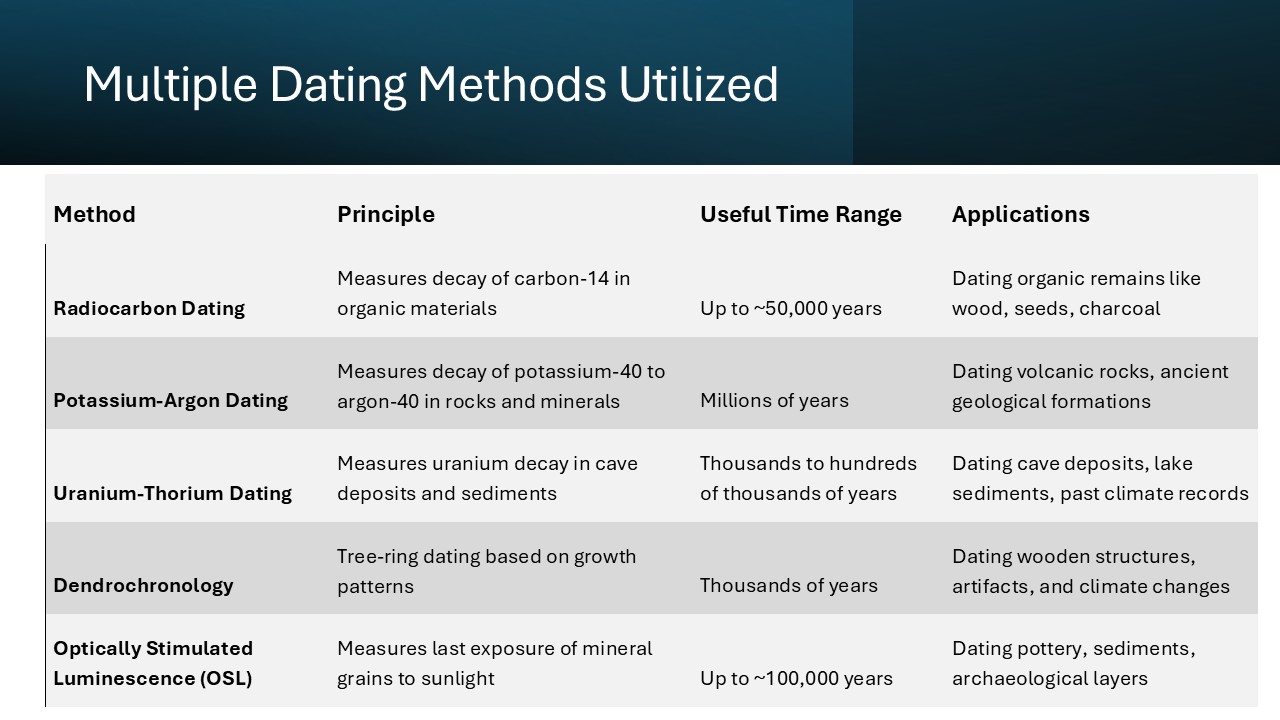

When it comes to figuring out how old these ancient settlements are, scientists don’t rely on just one method. Instead, they use a diverse set of dating techniques many of which are independent of each other. It’s kind of like using multiple witnesses to corroborate a story – if they all agree, you can be pretty confident you’re getting the truth.

These methods aren’t just pulled out of thin air. They’re based on well-established principles of physics, chemistry, and biology. And here’s the crucial point: when we apply these different methods to the same site or artifact, they tend to give us very similar ages (Liritzis et al., 2013). For example, radiocarbon dating of organic materials might give a similar age to thermoluminescence dating of pottery from the same layer. When multiple independent methods point to the same age range, it significantly increases our confidence in the results. It’s a bit like getting a medical diagnosis – you’d feel a lot more confident if several different tests all pointed to the same conclusion.

Radiocarbon dating

Let’s start with one you’ve probably heard of: radiocarbon dating. This method is based on the fact that all living things absorb carbon from their environment, including a tiny amount of radioactive carbon-14. When an organism dies, it stops taking in carbon, and the carbon-14 starts to decay at a predictable rate. By measuring how much carbon-14 is left, we can figure out how long ago the organism died (Taylor and Bar-Yosef, 2016).

Radiocarbon dating is very useful for dating organic materials up to about 50,000 years old. That covers the full ranges or recorded human history (Bronk, 2008)! Over the years, scientists have refined this method, developing calibration curves to account for past variations in atmospheric carbon-14 and using accelerator mass spectrometry for more precise measurements. For sites like Jericho, radiocarbon dating of seeds, wood, and other organic remains has been crucial in establishing its chronology (Bruins and van der Plicht, 1995).

Other radiometric dating methods

Now, radiocarbon dating is fantastic, but it’s not the only tool in our chronological toolbox. For older samples or inorganic materials, we’ve got other radiometric methods that can take us even further back in time. Take potassium-argon dating, for instance. This method is like the tortoise to radiocarbon’s hare – it’s based on the much slower decay of potassium-40 into argon-40. This allows us to date rocks and minerals that are millions of years old (McDougall and Harrison, 1999).

Another technique is uranium-thorium dating. This one’s particularly useful for cave deposits like stalagmites, which can provide us with records of past climate changes. In the Dead Sea region, uranium-thorium dating has been used to date salt deposits, providing insights into past lake levels and climate conditions (Torfstein et al., 2008). These methods, along with others like argon-argon dating, give us multiple independent ways to check and cross-verify the ages of geological and archaeological materials.

Non-radiometric dating methods

We also have a whole suite of non-radiometric dating methods that don’t rely on measuring radioactive decay at all. One of my favorites is dendrochronology – tree-ring dating. By matching patterns in tree rings, scientists can build chronologies stretching back thousands of years. It’s like nature’s own barcode system! In the Jordan Valley, dendrochronology has been used to date wooden artifacts and structures, providing precise calendar dates (Kuniholm et al., 1996).

Yet another non-radiometric technique is optically stimulated luminescence (OSL). This method measures when mineral grains were last exposed to sunlight, making it great for dating things like pottery and sediments. OSL has been particularly useful in the Dead Sea region for dating lake sediments and archaeological layers (Porat et al., 2010). These non-radiometric methods provide independent checks on our radiometric dates, adding another layer of confidence to our chronologies.

So, what’s the bottom line here? When we look at all these different dating methods – radiocarbon, potassium-argon, uranium-thorium, dendrochronology, OSL, and more – we see something remarkable. They all tend to converge on similar dates for our ancient sites. This consistency gives us a robust understanding of when these ancient settlements were occupied. It’s not just one method making a claim, but multiple independent lines of evidence all pointing in the same direction. I know it can be challenging when scientific evidence seems to conflict with a particular interpretation of Scripture. But I’d encourage you to consider the strength of this multi-faceted evidence. After all, if we believe that God is the author of both Scripture and nature, shouldn’t we expect them to ultimately agree? Perhaps the apparent conflict is an invitation to dig deeper, to expand our understanding of both the Bible and the world around us.

Synthesis and Implications

As we draw together the threads of evidence from archaeology, geology, and paleoclimatology, a compelling picture emerges of the Jordan Valley’s deep history. This synthesis not only challenges young-earth creationist interpretations but also invites us to marvel at the intricate ways in which God has shaped our world over vast periods of time.

What strikes me most about the evidence we’ve explored is the remarkable consistency across different fields of study. In addition to the dating methods discussed above, archaeological findings, geological processes, and climate records all point to a history of the Jordan Valley that extends far beyond the 4,350-year timeline proposed by young-earth creationism.

Moreover, there is genetic evidence from plant and animal domestication that corroborates these long timelines as well. The gradual changes we see in wheat, barley, and animal genomes simply cannot be compressed into a few centuries without invoking rates of change that we never observe in nature.

As a Christian who takes both faith and science seriously, I find this convergence of evidence deeply compelling. It suggests that we’re uncovering genuine truths about our world’s history—truths that reflect the intricate processes through which God has shaped creation.

The Challenge of Timeline Compression

Attempting to compress the evidence we’ve seen into a young-earth timeline creates insurmountable problems. Consider the following, many of which we have already explored:

- Cultural Development: The progression from simple stone tools to complex agricultural societies involves countless incremental innovations. Compressing this into a few centuries would require unrealistic rates of cultural evolution.

- Geological Processes: The formation of the Jordan Rift Valley, the deposition of massive sediment layers, and the creation of features like travertine deposits and speleothems all require timescales far beyond what a young-earth model allows.

- Climate Fluctuations: The climate records preserved in cave formations show multiple cycles of warming and cooling over tens of thousands of years. These cycles align with known astronomical variations that occur over long periods.

- Genetic Changes: The domestication of plants and animals involves genetic changes that accumulate slowly over many generations. Accelerating this process to fit a young-earth timeline would require mutation rates far higher than anything we observe.

Trying to squeeze all of this evidence into a 4,350-year timeline isn’t just difficult—it requires us to discard fundamental principles of science and invoke speculative mechanisms for which we have no evidence.

Importance of Accurate Historical Understanding

As Christians, why should we care about these ancient timelines? I believe there are several important reasons:

- Integrity of Faith and Reason: By engaging honestly with scientific evidence, we demonstrate that our faith is not threatened by empirical investigation. This can be a powerful witness in a world that often sees faith and science as incompatible.

- Appreciation of God’s Methods: Understanding the long, intricate processes through which God has shaped our world can deepen our awe of His creativity and patience. It invites us to see creation as an ongoing process rather than a one-time event.

- Environmental Stewardship: Recognizing the long history of our planet and the gradual processes that shape it can inform our approach to environmental issues. It reminds us of our responsibility to care for a world that God has been crafting for millions of years.

- Humility in Interpretation: The evidence we’ve explored challenges us to hold our interpretations of Scripture—particularly in areas that intersect with the natural world—with humility. It reminds us that God’s ways are often more complex and mysterious than our initial understanding might suggest.

Conclusion

As Christians, we must ask ourselves: How do we reconcile this overwhelming evidence with our understanding of Scripture? Is it possible that our interpretation of Genesis needs to be reconsidered in light of what we observe in God’s creation?

As we ponder these geological time capsules, we’re left with a profound appreciation for the deep history recorded in the rocks of the Jordan Valley. It’s a history that stretches far beyond written records, beyond even the earliest human settlements, inviting us to expand our understanding of time and our place within it.

For those of us who hold the Bible paramount, this evidence challenges us to think deeply about how we interpret Scripture. Could it be that God’s methods of creation are more intricate and time-consuming than we initially thought? Might our understanding of biblical chronology benefit from the insights provided by these silent witnesses in stone?

I believe that accepting the scientific evidence for an old earth doesn’t diminish the power or truth of Scripture. Instead, it can enhance our appreciation for the depth and complexity of God’s creative work. It invites us to read Genesis not as a scientific textbook first but as a profound theological statement about God’s relationship with creation and humanity’s place within it. There are difficult questions to be asked and we will explore many of these in upcoming part of this series.

As we wrestle with these questions, let’s remember that our goal is truth—both scientific and spiritual. By engaging honestly with the evidence before us, we honor the God of truth and deepen our appreciation for the wonders of His creation.

References

Bar-Matthews, M., Ayalon, A., Gilmour, M., Matthews, A., & Hawkesworth, C. J. (2003). Sea–land oxygen isotopic relationships from planktonic foraminifera and speleothems in the Eastern Mediterranean region and their implication for paleorainfall during interglacial intervals. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 67(17), 3181-3199.

Bar-Yosef, O. (1986). The walls of Jericho: An alternative interpretation. Current Anthropology, 27(2), 157-162.

Bronk Ramsey, C. (2008). Radiocarbon dating: revolutions in understanding. Archaeometry, 50(2), 249-275.

Bruins, H.J. and van der Plicht, J. (1995). Tell es-Sultan (Jericho): Radiocarbon results of short-lived cereal and multiyear charcoal samples from the end of the Middle Bronze Age. Radiocarbon, 37(2), 213-220.

Byrd, B. F. (2005). Reassessing the emergence of village life in the Near East. Journal of Archaeological Research, 13(3), 231-290.

Frumkin, A., Bar-Matthews, M., & Vaks, A. (2011). Paleoenvironment of Jericho and its vicinity. In A. Nigro (Ed.), Jericho and the Chronology of the Levant (pp. 103-128). Rome: Sapienza University.

Garfunkel, Z., & Ben-Avraham, Z. (1996). The structure of the Dead Sea basin. Tectonophysics, 266(1-4), 155-176.

Hirschfeld, Y. (2006). The Ein Gedi Excavations II: Final Report (1996-2002). Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society.

Kenyon, K. M., & Holland, T. A. (1981). Excavations at Jericho, Volume 3: The Architecture and Stratigraphy of the Tell. London: British School of Archaeology in Jerusalem.

Kuniholm, P.I. (2001). Dendrochronology and other applications of tree-ring studies in archaeology. In D.R. Brothwell and A.M. Pollard (eds.), Handbook of Archaeological Sciences, 35-46. John Wiley & Sons.

Lev-Yadun, S., Gopher, A., & Abbo, S. (2000). The cradle of agriculture. Science, 288(5471), 1602-1603.

Liritzis, I., Singhvi, A. K., Feathers, J. K., Wagner, G. A., Kadereit, A., Zacharias, N., & Li, S. H. (2013). Luminescence dating in archaeology, anthropology, and geoarchaeology: An overview. Springer Science & Business Media.

Magness, J. (2021). The Archaeology of Qumran and the Dead Sea Scrolls. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing.

McDougall, I. and Harrison, T.M. (1999). Geochronology and Thermochronology by the 40Ar/39Ar Method. Oxford University Press.

Nadel, D., & Werker, E. (1999). The oldest ever brush hut plant remains from Ohalo II, Jordan Valley, Israel (19,000 BP). Antiquity, 73(282), 755-764.

Porat, N., Duller, G.A.T., Amit, R., Zilberman, E., and Enzel, Y. (2009). Recent faulting in the southern Arava, Dead Sea Transform: Evidence from single grain luminescence dating. Quaternary International, 199(1-2), 34-44.

Rast, W. E., & Schaub, R. T. (2003). Bab edh-Dhra: Excavations at the Town Site (1975–1981). Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns.

Rollefson, G. O., & Kafafi, Z. (2007). The rediscovery of the Neolithic period in Jordan. In T. E. Levy, P. M. Michèle Daviau, R. W. Younker & M. Shaer (Eds.), Crossing Jordan: North American Contributions to the Archaeology of Jordan (pp. 211-218). London: Equinox.

Taylor, R. E., & Bar-Yosef, O. (2016). Radiocarbon dating: an archaeological perspective. Routledge.

Torfstein, A., Gavrieli, I., Katz, A., Kolodny, Y., & Stein, M. (2008). Gypsum as a monitor of the paleo-limnological–hydrological conditions in Lake Lisan and the Dead Sea. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 72(10), 2491-2509.

Valla, F. R. (1995). The first settled societies – Natufian (12,500-10,200 BP). In T. E. Levy (Ed.), The Archaeology of Society in the Holy Land (pp. 169-187). London: Leicester University Press.