In our exploration of the Dead Sea basin’s geological history, we’ve uncovered evidence of multiple desiccation events and significant fluctuations in lake levels over hundreds of thousands of years. These findings, derived from sediment cores and various dating methods, paint a complex picture of the region’s climatic and hydrological past. As we saw previously, this presents a significant challenge to any advocate of young-earth creationism.

How have young-earth creationists responded to this evidence? Despite being an obvious geological feature with a direct connection to the scriptures, young earth creationists have paid little attention to its origins. This is surprising given their many books, papers and videos about the origins of the Grand Canyon, Hawaiian Islands, and large mountain chains. When mentioned in creationist’ literature, the treatment is superficial, only referencing the surficial features of the modern Dead Sea without addressing its origins. One would think that a place which scriptures providence eye-witness testimony would be where creationists would go first to provide evidence of its recent origins.

Informally, I have heard young-earth proponents in conversation suggest what is the most natural, and objectively only, alternative hypothesis from their perspective. They have proposed the Dead Sea’s salt deposits are the result of the evaporation of seawater left behind after a global flood—specifically, Noah’s Flood as described in biblical accounts.

They propose that floodwaters were left-over from Noah’s Flood leaving the Dead Sea basin filled with saltwater, which then evaporated rapidly over a few hundred years, leaving behind substantial salt deposits. The “few hundred years” is a critical part of the hypothesis since the scriptures records the presence of the Dead Sea at or near its current position with cities deep within the Dead Sea basin by 2100 BCE (4100 years-ago). Additional salt accumulation over the approximately 4,350 years since the flood is attributed to ongoing evaporation of inflowing waters, such as those from the Jordan River.

This raises a critical question: Can a single evaporation event, followed by a few millennia of additional salt input, account for the approximately 2,000 feet (600 meters) of halite deposits observed in the Dead Sea basin? And this doesn’t include the deposition of another15,000+ feet of clays, silts and marlstone under Jordan Valley and Dead Sea.

But does this hypothesis hold water—or should I say, hold salt!? To test this we will critically examine this hypothesis by calculating the amount of salt that could be deposited from a single evaporation event. We’ll use established scientific principles and data to assess whether the proposed mechanism can account for the observed 2,000 feet (about 610 meters) of halite deposits in the Dead Sea basin. Through this analysis, we aim to determine the plausibility of the young-earth explanation considering empirical evidence.

Before continuing it is important to know that the values of 2000 feet and the total volumes of precipitated salts in the Dead Sea basin are intended to be underestimates of the total salt deposits that young-earth creationist must explain. Any difficulties that these calculations suggest for the young-earth viewpoint should therefore be seen as a minimum level of difficulty.

Calculating Salt Deposition from a Single Evaporation Event

To evaluate the young-earth hypothesis, we begin by understanding the properties of average seawater, which is crucial for calculating potential salt deposition. We will be assuming that the water in the Dead Sea basin immediately after the flood was no saltier than today’s sea water. Again, this is almost certainly an overestimate of the salt contraction as most creationists suggest the Flood waters were somewhere in between what is today fresh and sea water.

Sea water has a typical salinity of about 35 parts per thousand (‰), meaning that in every kilogram of seawater, there are approximately 35 grams of dissolved salts. This translates to a salinity of 3.5% by weight. The majority of these dissolved salts consist of sodium chloride (NaCl), which accounts for about 85% of the total salinity. Other components include magnesium, calcium, potassium, sulfate, and various trace elements (Millero et al., 2008).

Estimating the Thickness of the Salt Layer from Complete Evaporation of the Dead Sea Basin

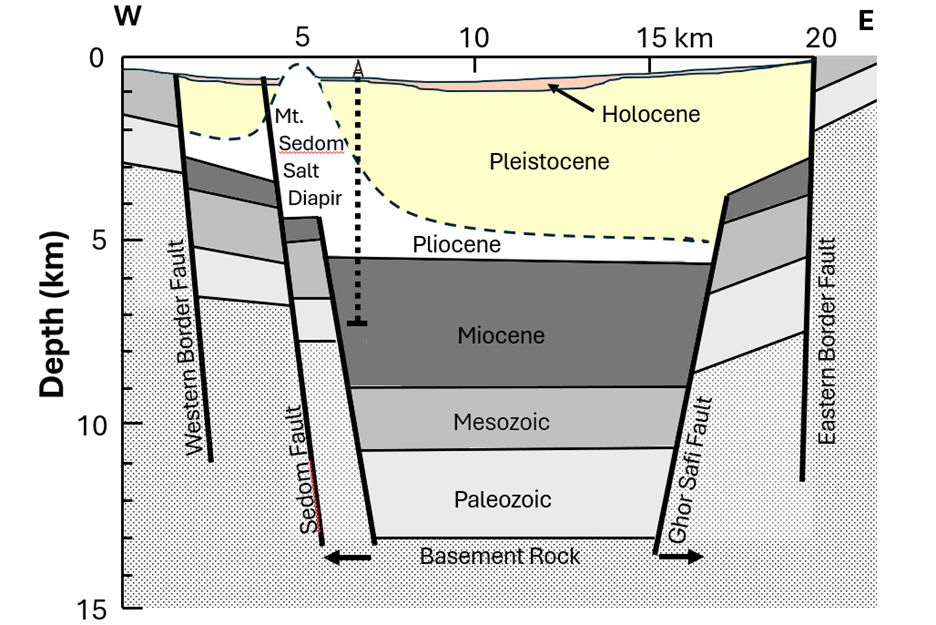

To determine the thickness of the salt layer that would result from the complete evaporation of the Dead Sea basin filled with seawater, we start by considering the basin’s dimensions as large rhombic prism with dimension of length: 80 kilometers, width: 15 kilometers, depth: 0.6 kilometers. Yes, we are going to stick with metric system for the primary calculations of depth, volume and density and will convert to more familiar unit in the final assessment. Also, we recognize that treating the basin as a rhombic prism is simplistic. In reality there are deeper portions and area that are much less wide than others this is a good first-order approximation of the volume that is likely overestimates the total volume and should be more favorable to the young-earth timeline we will be testing.

By multiplying these dimensions, we calculate the total volume of the basin to be approximately 720 cubic kilometers (80 km × 15 km × 0.6 km). This volume is equivalent to 720 billion cubic meters of seawater.

Seawater has an average salinity of about 3.5%, meaning that 3.5% of its mass consists of dissolved salts, primarily sodium chloride (NaCl) (Millero et al., 2008). The density of seawater is approximately 1,025 kilograms per cubic meter (UNESCO, 1981). Multiplying the total volume of seawater by its density gives a total mass of about 738 trillion kilograms of seawater in the basin.

Calculating 3.5% of this mass, we find that the total mass of dissolved salts in the basin is approximately 25.83 trillion kilograms. To determine the volume of salt that would precipitate upon complete evaporation, we use the density of halite, which is about 2,170 kilograms per cubic meter (Haynes, 2011). Dividing the total mass of salt by the density of halite yields a salt volume of approximately 11.9 billion cubic meters.

Next, we calculate the area over which this salt would be deposited, which is the surface area of the basin—80 kilometers in length and 15 kilometers in width—totaling 1,200 square kilometers or 1.2 billion square meters. Dividing the volume of salt by the area results in an average salt layer thickness of approximately 9.9 meters.

Therefore, if the Dead Sea basin with these dimensions were completely filled with seawater and then entirely evaporated, it would leave behind a salt layer approximately 10 meters (33 feet) thick. This calculation provides a quantitative understanding of the potential salt accumulation from such an event. In reality the salt would not be deposited evenly across 1200 square kilometers, the total surface area of the idealized rectangular basin. Rather it would only precipitate out of the water at the point when most of the water had evaporated and a lake similar to the Dead Sea today, had formed. Therefore, most of the salt would be deposited in an area ½ the size of that basin.

So, it is possible that 20 meters (66 feet) of the 600 meters of halite rock found deposited below the deep basins of the northern and southern portions of the Dead Sea and extended up under the Jordan River could have been deposited in a single evaporative event. To achieve the 600 total meters the basin would have to fill and evaporate 30 times!

Surely this would take a considerable amount of time and this doesn’t account for the other 15+ thousand feet of evaporites (salt, gypsum and others) and sediment deposited in the deep basins. It should also be noted that the most significant “pure” salt deposits are found more than 10,000 feet below the surface of the basin today. These are the salts that have flowed up through the overlying rock to form Mt. Sedom.

Estimating the Time Required for Complete Evaporation of the Dead Sea Basin

You might wonder – just how long would it take to evaporate the entire Dead Sea basin assuming it started full of salt water. A simple calculation under ideal conditions suggest not as long as you might think. However, this simple calculation belies the complexities of hydrological dynamic of this region. But its best to start with the optimal scenario to find the max rate restrictions on the age of the Dead Sea basin salt deposits.

To determine how long it would take for the entire volume of seawater in the Dead Sea basin to evaporate under ideal conditions, we start by considering the idealized basin’s dimensions as before: 80 kilometers in length, 15 kilometers in width, and 600 meters in depth. Another important caveat to this simple scenario is that there is no new input of water to the basin. This configuration results in a total volume of approximately 720 cubic kilometers of seawater, which is equivalent to 720 billion cubic meters (Haynes, 2011).

Under ideal conditions of 5% relative humidity and a continual temperature of 40°C (104 F), evaporation rates would initially be very high due to the significant vapor pressure deficit between the water surface and the surrounding air (Shaw et al., 2015). Low humidity and high temperatures accelerate the evaporation process, as dry air can absorb more water vapor.

However, as evaporation progresses, the salinity of the remaining water increases. Starting from an initial salinity of 3.5%—the average salinity of seawater—the concentration of dissolved salts becomes higher as water evaporates, leaving the salts behind. This increase in salinity affects the evaporation rate because higher salt concentrations lower the vapor pressure of the water, making it less prone to evaporation (Garrison, 2016).

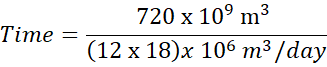

Initially, the evaporation rate might be around 10 to 15 millimeters per day under these extreme conditions (Rosen, 1994). Over the basin’s surface area of 1,200 square kilometers (derived from its length and width), this would equate to an evaporation volume of approximately 12 to 18 million cubic meters per day.

All together we can use this formula to calculate the length of time to evaporate the entire basin from a full starting point:

At a constant maximal evaporation rate, which is highly unrealistic, the entire volume could evaporate in 100 to 165 years!

However, this is an extremely simplified estimation that does not account for the decreasing evaporation rate due to rising salinity. As the water becomes more saline, the evaporation rate declines because the vapor pressure of the solution decreases. When the salinity approaches saturation levels—around 26% for sodium chloride—the evaporation rate diminishes significantly, and salt begins to precipitate out of the solution (Ophir & Gutman, 1991).

Considering this effect, the overall time required for complete evaporation would be substantially longer than initial calculations suggest. The evaporation process slows progressively, extending the timeframe from mere months to several years (Anati, 1999). When you consider that I reality the surface area of the basin shrinks as the water lowers down the basin this will also significantly decrease the evaporation potential. Putting these factors together this extends the ideal evaporative time to many hundreds of years

But hundreds of years is still highly idealistic. The most obvious problem is that the drainage area of the Dead Sea basin will continue to provide an influx of water to the basin even as the water is evaporating. Obviously, if the water inputs, which include the Jordan and other rivers along with many natural springs and rainfall, equal the evaporation output there would be no change in the water level in the basin. Even at today’s historically low influx of freshwater from precipitation and inflowing rivers this is enough to slow the rate of fall of the Dead Sea water to only a meter per year (Shaw et al., 2015). If the basin started full it would take 400 years to reach its present level under today’s extreme conditions.

If we need to evaporate 30 volumes of the Dead Sea basin to account for the salts preserved deep below the surface this we need to fill the basin 30 times and evaporate it all away between each filling. Our calculations suggest that if this happened one after another it would take minimally 30,000 years. The sedimentary record in the deep basin tells us that the salts were not deposited in successive block but rather with long periods of normal depositions of sediments during long high stands (such as we say with the Lake Lisan sediments and shorelines). To account for these observations, we need to push out timeline significantly.

Table 1. Environmental Conditions Affecting Evaporation and Salt Deposition

| Parameter/Condition | Value/Range | Impact on Evaporation/Deposition |

| Temperature | ~40°C (104°F) | High temperatures accelerate initial evaporation rates. |

| Relative Humidity | ~5% (idealized condition) | Low humidity increases the evaporation rate; however, this ideal condition is not sustained as salinity rises. |

| Initial Evaporation Rate | 10–15 mm/day | Supports rapid early-stage water loss; actual rates decline as dissolved salt concentrations increase. |

| Effect of Increasing Salinity | Progressive reduction | Higher salinity lowers water vapor pressure, reducing evaporation efficiency and prolonging the process. |

| Basin Surface Area (for deposition) | 1,200 km² (full); 600 km² (reduced) | Evaporation over a smaller area can effectively double the local deposit thickness compared to uniform distribution. |

Assessing Additional Salt Accumulation Over 4,350 Years

But what about salt input over time? While water from the Jordan River and other sources would slow the Dead Sea’s evaporation rate, young-earth advocates might argue that I’ve overlooked the ongoing contributions of dissolved salts from these sources. Could salt accumulation over 4,350 years since Noah’s Flood account for some or all of the massive salt deposits we observe today? Let’s analyze this possibility.

The Jordan River begins at the base of Mount Hermon, where several streams converge, and flows 251 kilometers (156 miles) south to the Dead Sea. Historical records show an average annual flow of about 1.3 billion cubic meters (Lensky et al., 2005). Though modern water diversion for agriculture and domestic use has significantly reduced this flow, the river continues to transport dissolved salts to the Dead Sea.

As it flows, the Jordan River accumulates dissolved minerals from surrounding rocks, including calcium, magnesium, potassium, chloride, and sulfate ions. Under natural conditions, the river carries approximately 1 gram of total dissolved solids (TDS) per liter (Farber et al., 2004). While this concentration appears modest compared to seawater, it represents a significant salt contribution over time.

Let’s calculate the annual salt input from the Jordan River:

Annual salt contribution = Annual flow × TDS concentration = 1.3 billion cubic meters × 1 gram/liter = 1.3 million metric tons of dissolved salts per year

Over 4,350 years – the time since Noah’s Flood according to young-earth chronology – this would amount to approximately 5.66 trillion kilograms of salt. This represents about 18% of the 31.53 trillion kilograms of salt that would precipitate from a single filling of the basin with seawater.

To determine how much additional halite thickness this would create, we use halite’s density of 2,170 kilograms per cubic meter (Haynes, 2011). Distributing this volume across the Dead Sea basin (approximately 1,440 square kilometers) would add only about 1.8 meters (6 feet) of halite. Even if we concentrate this deposition in the deeper basin areas as the lake shrinks, we estimate no more than 3.6 meters (12 feet) of additional salt accumulation over 4,350 years.

Combined Salt Deposition and Geological Observations

Adding the halite thickness from the hypothetical single evaporation event (about 20 meters or 66 feet) to the riverine contribution over 4,350 years (approximately 3.6 meters or 12 feet) yields a total potential halite layer of around 13.6 meters (approximately 78 feet). This combined thickness is significantly less than the observed 610 meters (2,000 feet) of halite deposits found in the Dead Sea basin (Stein et al., 2010).

Moreover, it’s important to note that most dissolved salts carried by the Jordan River would precipitate as halite. Some salts may remain dissolved in the water, while others could form different mineral deposits such as gypsum or aragonite. This further reduces the actual halite accumulation from riverine inputs.

Just thinking about the halite and gypsum deposits in the dead sea basin which exceed 6000 feet all together, the near pure halite deposits form under conditions of extreme and prolonged evaporation, when the concentration of dissolved salts in the basin’s waters reaches levels at which sodium chloride becomes supersaturated. In such hyperarid environments, characterized by high temperatures and very low humidity, water loss is so rapid that the remaining brine becomes highly concentrated in sodium and chloride ions. This scenario typically occurs when freshwater inputs are minimal or absent, allowing the evaporative process to proceed unimpeded. Under these conditions, the brine chemistry evolves to favor the precipitation of nearly pure halite, resulting in thick, uniform layers that testify to a sustained period of intense evaporative activity.

In contrast, gypsum deposition is favored under slightly less extreme conditions, where evaporation remains significant but is moderated by intermittent freshwater influx or less severe climatic conditions. Gypsum—a hydrated calcium sulfate—precipitates when the concentrations of calcium and sulfate ions reach critical levels in a moderately concentrated brine. These conditions may prevail during transitional phases in the basin’s hydrological cycle, such as following a period of halite deposition or during episodes of increased runoff that dilute the brine enough to prevent immediate halite precipitation. The alternation between halite and gypsum layers within the stratigraphic record thus reflects shifts in basin conditions, with pure halite indicating periods of sustained aridity and gypsum marking intervals when freshwater input or milder evaporation allowed for a different suite of minerals to precipitate. This cyclic interplay of depositional environments provides key insights into the dynamic evolution of the basin’s hydrology and climate over time.

Lastly, there are other deposits in addition to salts, the Jordan River and other tributaries contribute sediments to the Dead Sea valley floor. These sediments, which include clays, silts, and other particulate matter, help account for the substantial deposits found in the basin. However, accumulating the estimated 6,000 meters (approximately 20,000 feet) of post-Miocene sediment observed in the deepest parts of the basin over a period of just 4,350 years presents significant challenges when considering sedimentation rates and geological processes (Garfunkel & Ben-Avraham, 1996).

Table 2. Summary of Salt Input Sources and Their Estimated Contributions

| Salt Input Source | Estimated Salt Mass Contribution | Equivalent Halite Deposit | Notes/Assumptions |

| Complete Basin Evaporation (Seawater Flood) | Approximately 25.8 trillion kg (from 720 km³ of seawater at 3.5% salinity) | ~10 m if uniformly distributed over 1,200 km²; up to ~20 m if concentrated over half the basin’s area | Assumes seawater density of 1,025 kg/m³ and halite density of 2,170 kg/m³. The value represents the salt available in one full basin filling. |

| Riverine Input (Jordan River) | ~1.3 × 10⁹ kg/year; approximately 5.66 trillion kg over 4,350 years | ~1.8 m when evenly distributed; possibly up to ~3.6 m if focused in deeper portions | Based on an annual flow of ~1.3 billion m³ and a total dissolved solids (TDS) concentration of ~1 g/L. This input accounts for roughly 18% of the salt from a full evaporation. |

| Multiple Evaporative Cycles (Cumulative Effect) | 30 full basin cycles (each similar to a complete evaporation event) | ~600 m total observed deposit (30 cycles × ~20 m per cycle) | The observed ~600 m (2,000 ft) of halite implies that around 30 such cycles would be necessary. This represents a minimum timescale (~12,000 years if cycles occurred consecutively). |

| Mediterranean Seawater Influx (Ancient Connection) | Not quantitatively estimated | Not directly quantified; essential to explain deep, pure halite deposits beyond the shallow evaporite layers | This process describes a sustained “salt conveyor belt” where periodic connections to the Mediterranean provided a continuous influx of seawater, enhancing overall salt deposition. |

The Mediterranean Connection: A Key to Understanding Deep Salt Deposits

We’ve reached a pivotal point in our exploration of the Dead Sea’s history. Our calculations have shown that neither a single flood-related evaporation event nor thousands of years of river input can explain the massive salt deposits buried beneath the Dead Sea. Like a detective facing a seemingly impossible crime, we must look for additional clues – and those clues point us toward an ancient connection between the Dead Sea basin and the Mediterranean Sea.

This connection isn’t merely speculative. Geological evidence reveals that early in its history, the Dead Sea basin was part of a complex system of lagoons and shallow seas that periodically connected to the Mediterranean. This discovery helps solve one of our biggest puzzles: the source of all the very large pure salt deposits buried more than 2km below the bottom of the Dead Sea.

To understand how the Mediterranean connection worked, we first need to remind ourselves of how the Dead Sea basin developed. Picture the landscape of the region around 20 million years ago. The dramatic rift valley we see today didn’t exist. Instead, the rocks that now lie thousands of feet below the Dead Sea’s surface were continuous with those we see in the surrounding plateaus. This land was initially not much above sea level, having not yet been pushed up by the upwelling mantle that would later cause the extensive rift system we see today.

As tectonic forces began pulling the Arabian and African plates apart, a series of events unfolded. Initial rifting created a shallow depression, which gradually deepened as blocks of Earth’s crust subsided along fault lines. At the same time, the land east of the fault was being pushed up. The widening crack created space for water to accumulate, and the basin continued to deepen over millions of years. During these early stages, just north of where Mount Carmel now projects into the Mediterranean Sea, a low-elevation corridor existed that would periodically allow seawater to flow into the developing Dead Sea basin.

The Salt Accumulation Process

This is where the story gets really interesting. Think of the early Dead Sea basin as nature’s salt-making factory, operating with remarkable efficiency. The process worked like a giant natural distillation system. Mediterranean seawater flowed through the northern corridor into the shallow, warm basin. Under the hot, arid climate, this water would rapidly evaporate, causing dissolved salts to become more and more concentrated. When the remaining water became supersaturated, salt would precipitate out and settle to the basin floor. More seawater would flow in from the Mediterranean, bringing new dissolved salts, and the process would repeat.

What makes this mechanism so powerful is its continuous nature. Unlike our previous scenarios that relied on a single filling event or slow accumulation from river input, this “salt conveyor belt” could efficiently concentrate and deposit massive amounts of salt over long periods.

The early basin’s shallow depth allowed for efficient evaporation, while the region’s hot, dry climate promoted rapid evaporation. The connection to the Mediterranean provided a seemingly endless supply of new saltwater, and as the rift valley continued to subside, it created space for more deposits to accumulate.

Most importantly, this process would have operated under relatively calm, stable conditions. This explains one of the most striking features of the deep salt deposits – their remarkable purity. The thick layers of almost pure halite we find deep beneath the Dead Sea today require stable environments for deposition, quite different from the mixed sediments we would expect from catastrophic flood deposits.

Think of it like making sea salt in a solar evaporation pond. If you simply let seawater evaporate slowly and steadily, you get pure salt crystals. But if you stir up the pond or add soil and debris, you get a mixed deposit. The purity of the deep Dead Sea salt layers tells us they formed in a calm environment over long periods, not during chaotic flooding events.

Multiple Filling and Evaporation Events

Beyond the Mediterranean connection, another mechanism for salt accumulation involves multiple filling and evaporation cycles within the Dead Sea basin itself. We’ve already encountered evidence for one such massive water body: Lake Lisan (see Part IV), which occupied the basin during the late Pleistocene epoch (approximately 70,000 to 15,000 years ago) (Katz et al., 1977). Lake Lisan’s documented fluctuations in size and depth, reaching levels far above today’s Dead Sea, left behind substantial evaporite deposits including layers of halite and gypsum.

A Complex History of Salt Accumulation

The Dead Sea basin has functioned like Earth’s own laboratory for salt production, operating through distinct phases that we can read in its sedimentary record:

During wet periods, freshwater or brackish water would flood the basin, diluting existing brines while depositing silt and clay. As climate shifted toward aridity, evaporation would exceed inflow, concentrating the remaining water until it became supersaturated, forcing dissolved salts to precipitate out. These salts would settle to the basin floor, creating distinct mineral layers. This wet-dry cycle repeated countless times over hundreds of thousands of years, gradually building up the thick sequences of evaporites and sediments we observe today.

The Dead Sea Deep Drilling Project (DSDDP) has provided unprecedented insight into these cycles. Their cores reveal a geological diary of environmental changes – thick halite layers marking intense dry periods alternate with clastic sediments deposited during wetter times. Perhaps most surprisingly, organic-rich layers suggest periods when the Dead Sea supported much more life than we observe today. Each layer represents a different chapter in the basin’s long history (Neugebauer et al., 2014).

Dating methods including uranium-thorium, radiocarbon, and varve counting have established a detailed 200,000-year chronology of these changes. These dates correlate remarkably well with known global climate events like glacial and interglacial periods (Torfstein et al., 2015).

The basin’s evolution reflects an intricate dance between tectonic activity and climate change. Repeated subsidence of the valley floor created space for sediment accumulation, while orbital-driven climate fluctuations controlled water balance (Ben-Avraham et al., 2008; Stein, 2014). Adding further complexity, we see evidence that some salt deposits were later dissolved during fresher conditions and redeposited elsewhere. This means the current salt deposits likely underrepresent the total amount of salt that has cycled through the basin over time.

This dynamic history of deposition, dissolution, and redeposition speaks to a long and complex geological story that cannot be explained by a single flood event (Weinberger et al., 2006). The evidence points instead to multiple cycles operating over vast periods, shaping and reshaping the unique environment we observe today.

Implications for the Young-Earth Hypothesis

Having examined multiple potential mechanisms for salt accumulation in the Dead Sea basin – from a single post-Flood evaporation event to river inputs to Mediterranean connections – we find that none can account for the extensive halite deposits within a young-earth timeframe. The geological record instead reveals a complex history of repeated cycles of expansion, contraction, and salt deposition occurring over extended periods.

The processes responsible for accumulating 2,000 feet of halite require timescales far exceeding the young-earth model’s 4,350-year window. Multiple independent dating methods – including radiocarbon dating, uranium-thorium dating, and varve counting – consistently indicate ages extending back hundreds of thousands of years (Prasad et al., 2004). These dates align with the geological evidence for repeated cycles of Mediterranean connection and disconnection that we explored earlier.

Our analysis reveals three fundamental challenges to young-earth interpretations:

First, we face a time problem. Even under ideal conditions and accepting the Mediterranean connection mechanism, accumulating the observed salt deposits would require hundreds of thousands of years. No known natural mechanism could compress this process into a few centuries without violating basic physical and chemical principles. The pure nature of the deep salt deposits, as we discussed earlier, indicates slow, steady accumulation rather than rapid deposition.

Second, we encounter a process problem. While young-earth models often invoke unusual or unprecedented processes to explain geological features, the Dead Sea salt deposits show clear evidence of normal evaporative processes operating under conditions similar to what we observe today. The “salt conveyor belt” mechanism we described requires stable conditions over long periods to produce the pure halite layers we observe.

Third, we must consider the context problem. The salt deposits don’t exist in isolation – they’re part of a coherent regional story that includes the development of the Dead Sea rift, regional climate changes, sea level fluctuations, and tectonic movements. These elements work together in ways that require long periods of time and align with our understanding of the Mediterranean connection’s role in the basin’s evolution.

Our analysis highlights the importance of evidence-based reasoning in understanding Earth’s history. By integrating data from geology, chemistry, climatology, and geochronology, we’ve constructed a coherent explanation that aligns with observed phenomena and natural laws. This comprehensive approach not only enhances our understanding of the Dead Sea’s geological history but also reinforces the broader framework of Earth’s deep-time narrative.

Next up in Part X, we will summarize the ancient and young-earth interpretations of all the observations we have made from the Dead Sea basin and discuss another response by a young-earth creationist to one particular claim about the history of the Dead Sea: that it once dried up in the past.

References

Anati, D. A. (1999). The salinity of hypersaline brines: Concepts and misconceptions. International Journal of Salt Lake Research, 8(1), 55–70.

Farber, E., Pannatier, Y., & Arad, A. (2004). Hydrochemistry of the Jordan River. Journal of Hydrology, 289(1-4), 16-28.

Garfunkel, Z., & Ben-Avraham, Z. (1996). The structure of the Dead Sea basin. Tectonophysics, 266(1-4), 155-176.

Garrison, T. (2016). Oceanography: An Invitation to Marine Science (9th ed.). Cengage Learning.

Haynes, W. M. (Ed.). (2011). CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (92nd ed.). CRC Press.

Lensky, N. G., Dvorkin, Y., Lyakhovsky, V., Gertman, I., & Gavrieli, I. (2005). Water, salt, and energy balances of the Dead Sea. Water Resources Research, 41(12), W12418.

Millero, F. J., Feistel, R., Wright, D. G., & McDougall, T. J. (2008). The composition of Standard Seawater and the definition of the Reference-Composition Salinity Scale. Deep-Sea Research Part I: Oceanographic Research Papers, 55(1), 50-72.

Ophir, D., & Gutman, M. (1991). Evaporation measurements at the Dead Sea—An energy balance approach. Journal of Hydrology, 122(1-4), 239–247.

Rosen, M. A. (1994). Exergy analysis of evaporation. International Journal of Ambient Energy, 15(2), 63–68.

Shaw, E. M., Beven, K. J., Chappell, N. A., & Lamb, R. (2015). Hydrology in Practice (4th ed.). CRC Press.

Stein, M., Torfstein, A., Gavrieli, I., & Yechieli, Y. (2010). The deep Dead Sea drilling project (DSDDP): A window into the past, present, and future of the Dead Sea. GSA Today, 20(6), 4–9.

UNESCO. (1981). Background Papers and Supporting Data on the Practical Salinity Scale 1978. UNESCO Technical Papers in Marine Science, No. 37.